The simple checks every man should do for breast cancer

Professor Dorothy Ibifuro Makanjuola

- Published

- Lifestyle

Men can and do develop breast cancer, but late diagnosis means they face worse survival rates than women. Raising awareness and encouraging self-examination are crucial, writes Professor Dorothy Ibifuro Makanjuola

Breast cancer is almost always spoken of as a condition that affects women, yets that assumption has real and sometimes fatal consequences. Men can, and do, develop breast cancer, and while it accounts for only about one per cent of all cases, the disease in men is more likely to prove deadly because it is usually recognised far too late.

The reason men are less likely to develop breast cancer comes down to how breast tissue grows in the two sexes. Everyone is born with breast tissue, and it is this tissue that can become cancerous. In women, the hormones oestrogen and progesterone drive the growth of ducts and milk-producing glands, so the breast contains glandular tissue, ducts, and fat. In men, testosterone stops that development, leaving a breast made up mainly of fat and connective tissue, with only very small amounts of ductal and secretory tissue. Because most breast cancers begin in the ducts or glands, the risk for men is much lower — but it is not zero.

In the United Kingdom, around 390 men are diagnosed with breast cancer each year, compared with roughly 56,400 women. In the United States, the American Cancer Society predicts that in 2025 about 2,800 men will be diagnosed and 510 will die. Men face higher mortality because awareness is low, diagnosis is often delayed, and there are no routine screening programmes equivalent to those available to women.

Risk factors for male breast cancer include increasing incidence with age. A family history of breast cancer in either sex is an important risk factor. Mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, well known for their role in female breast cancer, are also important in men, as they encourage cancer cells to grow and spread. Exposure to higher levels of oestrogens relative to androgens is a significant risk factor.

Disorders where the balance of androgens to oestrogens is disrupted also increase the risk. That can include treatment with oestrogens or chromosomal disorders such as Klinefelter’s Syndrome, where an extra X chromosome raises oestrogen levels and produces more developed glandular tissue. Men with Klinefelter’s face a higher risk not only of the ductal carcinomas that are most common in men, but also of glandular cancers, which are otherwise unusual. Obesity is another contributor, since excess fat is associated with higher oestrogen levels. Previous radiation to the chest wall may further increase risk.

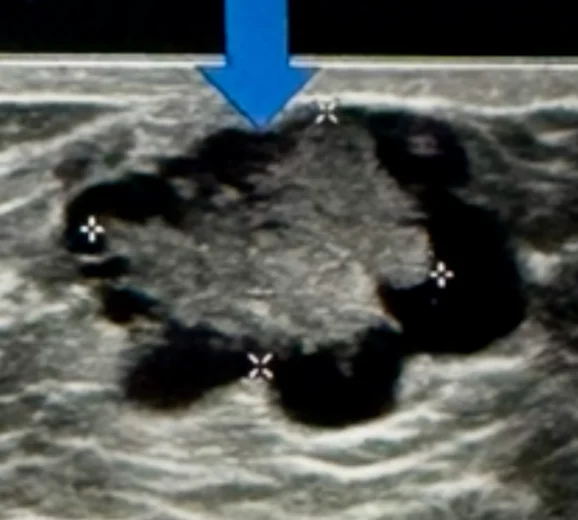

The disease usually presents in a characteristic way. The classic sign is a hard, immobile, painless lump beneath the areola. Benign breast tumours, by contrast, tend to be soft, mobile, and often painful, and are also located under the areola.

When cancer occurs in men with pre-existing gynaecomastia, diagnosis may be delayed because the tumour can be masked on clinical examination and may arise anywhere in the breast. Other warning signs include nipple retraction, puckering or discolouration of the skin, and nipple discharge that may be blood-stained.

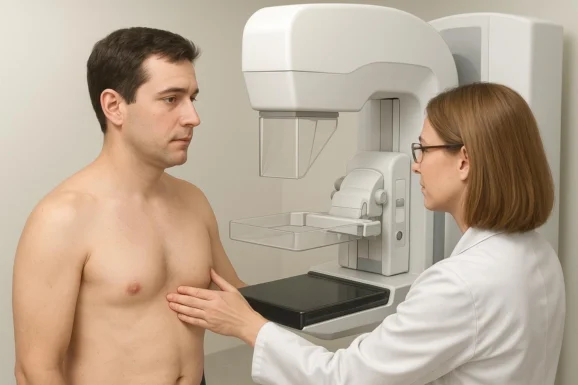

Early detection begins with self-examination. Men should check their chest wall, breast tissue, and armpits once a month, ideally in front of a mirror. They should look for swellings, asymmetry, secretions from the nipple, nipple retraction, and changes in the skin over the breast, including puckering, dimpling, or redness, and then palpate the area to feel for lumps. Any concerns should be reported promptly to a GP.

If something suspicious is found, medical imaging is used to investigate. Mammography, ultrasound, and sometimes MRI can distinguish between cancers and benign growths such as lipomas, haemangiomas, or fibroadenomas, but biopsy remains the definitive test.

There are four main types of breast cancer relevant to men. Ductal carcinoma in situ is confined to the ducts. Inflammatory breast cancer causes redness, swelling, and warmth of the breast. Invasive ductal carcinoma, which appears as a firm, painless lump, is the most common type in men. Paget’s disease of the nipple begins in the ducts beneath the nipple and presents with swelling and discolouration.

Treatment options are broadly the same as for women. Surgery, usually in the form of mastectomy or lumpectomy, is common, often followed by radiotherapy and hormonal therapy. In advanced disease, hormonal treatments may still be offered, although the response is usually poor.

Survival rates depend almost entirely on when the cancer is caught. If the tumour has not spread, five-year survival is close to 97 per cent. If it has metastasised to lymph nodes, bones, lungs, or the liver, that figure falls to about 20 per cent. Prognosis is also influenced by age, other health conditions, and genetic mutations such as BRCA2.

Preventive measures are important. Men with a strong family history should consider genetic counselling and ongoing surveillance, particularly where BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations are present. Keeping a healthy weight reduces risk, as does regular exercise, avoiding smoking, and limiting alcohol consumption.

Although male numbers are small compared with women, 390 British men and 2,650 American men are still being diagnosed each year, many too late to benefit from the best treatments. Male breast cancer may be rare, but it is deadly when overlooked. Older men, those with family histories, and those carrying high-risk mutations face particular danger.

Men must recognise that breast cancer does not affect women alone. Regular self-examination, prompt medical advice when changes are noticed, and greater vigilance from doctors are essential. Public health campaigns also need to speak to men as clearly as they do to women. Awareness determines outcomes: survival can be as high as 97 per cent when the disease is caught early, but it drops to around 20 per cent once it has spread.

Breast cancer in men is real, and greater awareness is the only way to improve survival.

Professor Dorothy Ibifuro Makanjuola is Professor and consultant in Radiology, specialising in gastrointestinal and women’s imaging. She is the Director of Women’s Imaging at the Specialised Women’s Hospital in King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. She holds an MB BS from the University of Ibadan and postgraduate radiology qualifications from Edinburgh and London. Professor Makanjuola has conducted significant research into female and male breast cancer

Read More: ‘Curium’s expansion into transformative therapy offers fresh hope against cancer’. Increased radioligand therapy options could transform cancer treatment by targeting tumours while reducing exposure to surrounding healthy tissue. Curium, a global leader in nuclear medicine, is moving to roll it out worldwide.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Need some downtime? Head to Nerja for some serious decompression

Need some downtime? Head to Nerja for some serious decompression -

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller (and it’s not what you think)

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller (and it’s not what you think) -

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways -

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus -

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism'

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism' -

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50 -

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom -

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living -

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius -

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj -

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic -

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream -

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day -

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life -

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split -

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic -

The bon hiver guide to Paris

The bon hiver guide to Paris -

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj -

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality -

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok -

The European road test: The Jeep Wrangler Rubicon

The European road test: The Jeep Wrangler Rubicon -

Rattrapante Mondiale – Split-Seconds Worldtimer

Rattrapante Mondiale – Split-Seconds Worldtimer -

Adaaran Select Meedhupparu & Prestige Water Villas: a Raa Atoll retreat

Adaaran Select Meedhupparu & Prestige Water Villas: a Raa Atoll retreat -

Heritance Aarah: an island escape crafted for exceptional family and couples’ stays

Heritance Aarah: an island escape crafted for exceptional family and couples’ stays -

Stanley Johnson in Botswana: a return to the wild heart of Southern Africa

Stanley Johnson in Botswana: a return to the wild heart of Southern Africa