Exploring France’s wildest delta: Julian Doyle on the trail of white horses, black bulls and the hidden history of the Camargue

Julian Doyle

- Published

- Lifestyle

On the Rhône delta, white horses gallop through the shallows, bulls graze in open fields, and flamingos colour the sky pink. Yet beyond its rice paddies and salt flats, the Camargue is also a place of legend, where pilgrims honour Saint Sara and local tradition even tells of Mary Magdalene’s arrival by boat. Monty Python editor and religious scholar, Julian Doyle, sets out to uncover how this remote corner of France became a haven for wildlife and a centre of centuries-old devotion

Think you know the south of France? Provence has its lavender fields, Marseille its bustling harbour, and the Riviera its yachts and celebrity beach clubs. But travel just along the coast and you’ll find a place most holidaymakers overlook: the Camargue.

Here the River Rhône fans out into the Mediterranean, creating a wild delta of lagoons, salt flats and marshes that covers some 360 square miles between Arles and Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. This is cowboy country, French-style: white horses gallop through the shallows, black bulls roam the open plains, and flamingos rise in their thousands to turn the sky pink. Rice paddies and salt pans stretch to the horizon, while small fishing villages cling to the coastline.

Unlike the Riviera, the Camargue offers no casinos or designer boutiques. Instead, it’s about open skies, hearty food and a way of life that has barely changed in centuries. Fog drifts over the reeds in the mornings, afternoons fill with migrating birds, and sunsets blaze across the marshes.

For many travellers it’s a complete surprise — a working, living landscape that feels closer to the American West than to Provence. And if you’re planning a trip, autumn and early winter are the perfect times to come, when the crowds are gone and the Camargue shows itself at its most dramatic.

What to see

You can reach the Camargue from several directions. From the north, most travellers come down from Arles, which has the best transport links by train and road. From the west, it’s accessible from Montpellier, while from the east you can approach via Marseille or Nîmes. Public transport is limited, so you’ll need a car to see the best of it.

Driving in from Arles, as I did, the road runs straight across the delta, with reed beds on either side and the water level shifting constantly. One stretch looks like a wide lagoon, the next like a drained marsh.

The first things most visitors look for are the white horses. They are small, muscular and well adapted to the wetlands, living in semi-wild herds but also used by the gardians, the mounted herdsmen of the Camargue. Not far behind are the black bulls, grazing on the open land. These are bred for the arenas of Nîmes and Arles, but in the Camargue you see them simply as part of the landscape.

Birdwatchers come for the flamingos and migratory species that pass through in their thousands. The easiest place to spot them is the Parc Ornithologique de Pont de Gau, just outside Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, where boardwalks lead past lagoons filled with herons, egrets and avocets. Autumn is the best time to see cranes, while winter brings large numbers of ducks and waders.

What to do

For many visitors, the best — and some say the only — way to experience the real Camargue is on horseback. Local riding schools and farms offer half-day or full-day treks across the salt flats, beaches and reed beds, allowing you to see the landscape as the gardians do. Rides usually start from small ranches outside Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer or Aigues-Mortes, where groups are matched with steady white horses accustomed to carrying beginners. More experienced riders can opt for longer hacks into the wetlands or along the coast. Expect to pay from around €40 for a two-hour ride. Riding one of these sturdy horses through shallow water at sunset, with flamingos lifting off in the distance, is considered one of the defining Camargue experiences and is worth every centime.

The region is also home to a unique sporting tradition: the course camarguaise. These contests, held in village and town arenas from spring to autumn, pit young men against bulls, but unlike Spanish bullfighting, the animals are never killed. Instead, nimble raseteurs dressed in white vault and dart around the bull, aiming to snatch rosettes tied between its horns. Here, it is the bulls who are the true stars, remembered and celebrated long after the raseteurs have retired. Posters for the season are plastered on village walls, and tickets are inexpensive compared to the bloodier Spanish corridas.

For those who want to see a full Spanish-style corrida, Nîmes is the place to go. About an hour’s drive north, the city’s Pentecost feria in May fills the streets with parades, music and food stalls — before culminating in the extraordinary sight of bullfights staged inside its Roman amphitheatre, one of the best preserved in the world. The same arena also hosts a September feria, making Nîmes one of the only places where modern matadors perform in an ancient gladiatorial setting. Yet opinion is divided locally, with some celebrating the feria as part of the city’s cultural identity, while others see it as an outdated ritual.

Adding to the region’s distinct character are its Gypsy communities, who speak and sing in Spanish. Their music — carried far beyond the Camargue by the world-famous Gipsy Kings — lends the villages another unmistakable rhythm.

For those who prefer quieter pursuits, the Camargue’s flat terrain is ideal for cycling. Bikes can be hired in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer or Aigues-Mortes, and routes take you past rice fields, vineyards and open marshes where you’ll see flamingos at close range. Even a short ride along the dyke roads gives you a sense of the scale and emptiness of the delta.

Eat and drink

The Camargue is a working landscape, and its food is straightforward, hearty and tied to what the land produces.

The region’s most distinctive staple is its red rice, grown in the paddies of the delta since the 19th century. Nutty and slightly chewy, it appears on menus everywhere — served simply with grilled fish, mixed into salads, or as the base for rustic stews. You’ll see packets of it for sale in supermarkets and farm shops, often marked with a protected designation of origin.

The signature dish is gardiane de taureau, a slow-cooked bull stew. Chunks of meat are simmered for hours in red wine with garlic, onions, olives and Provençal herbs until tender. It was originally prepared by gardians after long days working cattle, and today it’s found in restaurants from Saintes-Maries to Arles. Expect to pay around €18–€25 for a generous bowl, usually served with rice from the delta. In winter, farmhouse auberges serve it beside open fires, often alongside game such as wild boar or duck.

Seafood also features strongly. The coastline provides mussels, clams and oysters, while local fishermen supply eels and mullet. Look for menus offering tellines — tiny wedge clams cooked quickly in garlic and parsley, often eaten with bread and wine.

For something sweet, try navettes — small boat-shaped biscuits flavoured with orange blossom. They are linked to the legend of Mary Magdalene’s sea crossing and eaten in particular around Candlemas in February, though you’ll find them in bakeries year-round.

The Camargue also produces salt, harvested from the vast pans near Aigues-Mortes and Salin-de-Giraud. Driving past, you can see mounds of fleur de sel rising against the horizon, often tinted pink by microscopic algae. Many restaurants use the salt, and visitors can buy it direct from roadside stalls or shops in town.

To drink, the obvious choice is Costières de Nîmes wine, grown just beyond the marshes. Robust reds and crisp rosés pair well with stews and seafood. Local cafés usually offer carafes of house wine at good value, but you’ll also find bottles from small domaines in wine shops across the region.

Where to stay

Where you base yourself depends on what you want to experience.

Arles makes the most practical choice. Once a Roman capital, it is packed with ruins, museums and Van Gogh associations, yet it is also a lively Provençal town with good hotels and transport links. From here you can easily drive into the Camargue or take day trips further afield.

For a more immersive stay, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer offers a small-town seaside atmosphere. Its hotels and guesthouses range from simple pensions to boutique properties, and in May the town comes alive with pilgrims and celebrations.

Further inland, traditional mas farmhouses provide rustic guest rooms, sometimes combined with horse-riding or birdwatching packages. Staying on a farm allows you to see the working rhythms of the land: rice being harvested, bulls being herded, and meals shared around a communal table.

Off-season, prices drop, the light softens, and the Camargue feels even more mysterious. Some coastal businesses close until spring, but for those who value atmosphere over bustle, that is part of the appeal.

Faith and folklore

Every May, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer fills with one of Europe’s largest Roma pilgrimages. Communities travel from across the continent to honour Saint Sara la Noire, their patron saint, and her statue is carried from the church crypt down to the Mediterranean in a lively procession of music, flamenco dancing and prayer.

According to local tradition, the roots of this devotion stretch back almost two thousand years. In AD 43, Mary Magdalene, her sister Martha, her brother Lazarus and their companion Maximin were said to have fled the Holy Land by boat. Blown off course, they landed on this coast, then called Notre-Dame-de-la-Mer, and for centuries the town and its fortress-like church bore that name.

The story changed in the fifteenth century. Instead of the Bethany family, three other women — Mary Magdalene, Mary Jacob and Mary Salome — were placed at the centre of the tale, along with Sara. The church became Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, and over time Magdalene’s role was steadily reduced. Even today, souvenirs often show Sara with two Maries while omitting Magdalene entirely.

Sara remains central in the crypt, where pilgrims still gather around her effigy. Some regard her as part of the Black Madonna tradition that runs across southern France. Others believe she represents Magdalene herself, who as a Jewish woman of the first century would have looked very different from the pale European figures created in later centuries.

The Camargue legend links directly to other parts of France. Stained-glass windows at Chartres Cathedral show Magdalene stepping from a boat and preaching beside Maximin; similar images appear in Paris at Saint-Séverin. Even the foundation of Notre Dame de Paris has been associated with her.

Further along the Provençal trail, Martha is said to have settled at Tarascon, where her tomb is still shown. Magdalene, Lazarus and Maximin travelled on to Marseille. Lazarus became the city’s first bishop, while Magdalene is remembered preaching in the open air before retreating to a cave at Sainte-Baume, where she is believed to have spent her final years.

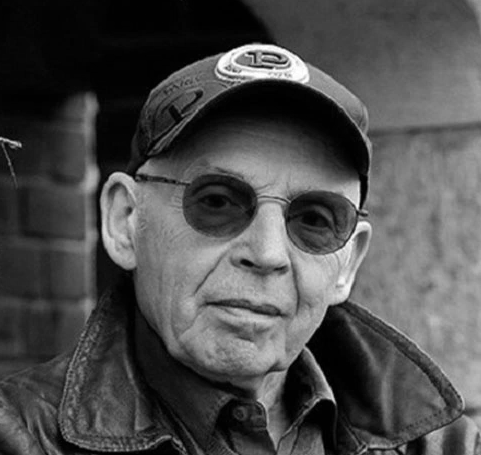

Julian Doyle is a British filmmaker, editor and writer whose career spans film, theatre and music. He worked closely with Monty Python, editing Life of Brian and The Meaning of Life, and handling special effects on Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Beyond Python, he collaborated with Terry Gilliam on Brazil and Time Bandits, and directed films including Love Potion and Chemical Wedding (co-written with Iron Maiden’s Bruce Dickinson). His music video work includes Kate Bush’s Cloudbusting and Iron Maiden’s Can I Play with Madness. Doyle is also a playwright and author, with credits ranging from Twilight of the Gods, a play about Wagner and Nietzsche, to a series of books exploring biblical history, including The Gospel According to Monty Python, Who Killed Jesus? and The Secret Life and Hidden Death of Judas the Galilean.

Read More: ‘I never expected the Spanish Inquisition. How bureaucracy turned my life into a Python sketch‘. When filmmaker Julian Doyle received a Home Office letter declaring his wife’s residency had “expired,” it felt like a scene from one of the Monty Python films he helped create. Now, as he faces the prospect of leaving his home and family in Britain, he reflects on how bureaucracy has become a parody of itself.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main Image: Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, southern France—historic heart of the Camargue region.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller (and it’s not what you think)

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller (and it’s not what you think) -

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways -

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus -

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism'

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism' -

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50 -

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom -

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living -

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius -

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj -

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic -

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream -

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day -

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life -

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split -

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic -

The bon hiver guide to Paris

The bon hiver guide to Paris -

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj -

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality -

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok -

The European road test: The Jeep Wrangler Rubicon

The European road test: The Jeep Wrangler Rubicon -

Rattrapante Mondiale – Split-Seconds Worldtimer

Rattrapante Mondiale – Split-Seconds Worldtimer -

Adaaran Select Meedhupparu & Prestige Water Villas: a Raa Atoll retreat

Adaaran Select Meedhupparu & Prestige Water Villas: a Raa Atoll retreat -

Heritance Aarah: an island escape crafted for exceptional family and couples’ stays

Heritance Aarah: an island escape crafted for exceptional family and couples’ stays -

Stanley Johnson in Botswana: a return to the wild heart of Southern Africa

Stanley Johnson in Botswana: a return to the wild heart of Southern Africa -

Germany’s Jewellery Museum in Pforzheim unveils landmark exhibition on dining culture

Germany’s Jewellery Museum in Pforzheim unveils landmark exhibition on dining culture