George Clooney-backed film tackles fake news epidemic

Michael Leidig

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

Friedrich Moser’s documentary How to Build a Truth Engine explores the worrying challenges of defining truth in a digital age dominated by misinformation and conspiracy theories, writes Mike Leidig

Few topics have generated as much fake news as the subject of fake news itself.

It is the easiest way to undermine any narrative that you don’t like: simply call it ‘fake news’.

That is perhaps the real significance of Austrian director Friedrich Moser’s George Clooney backed documentary How to Build a Truth Engine.

This compelling film peels away the layers of the onion and gets closer to the truth than anything I have seen before.

One of its great strengths comes from adhering to the journalistic tradition of listening to answers and following leads, rather than forcing the subject into a pre-constructed frame.

Moser has been working on topics related to freedom in the digital age since around 2011, inspired by events like WikiLeaks, Cablegate, and the Arab Spring.

After two films about mass surveillance, he shifted his focus to fact-checking software and investigative journalism.

However, the project almost collapsed when his primary text protagonist, Jan van Oort, dropped dead unexpectedly from a heart attack.

In Moser’s words, the “film was just bits and pieces that did not work as a story, though we tried very hard.”

At its core is the seemingly uncrackable problem: how do you ringfence truth in a post-truth era.

The breakthrough came when he shifted focus to include StoryMiner, software developed at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and the University of California, Berkeley, which can detect conspiracy theories on social media.

This led him to neuroscientist collaborators who revealed an entirely new layer of understanding.

Having written about fake news for more than a decade, I was familiar with many of the early arguments presented in the film and had heard of StoryMiner.

The team at UCLA suggested that Moser engage with their neuroscientist colleagues, which turned out to be a game-changer for the documentary.

Moser admitted: “When I started talking to the neuroscientists, it blew my mind.”

He realised that fact-checking alone could not solve the problem of fake news.

“Because what do you do if you have all the facts laid out, but people just don’t believe them?”, he explained.

“And this is why the neuroscience aspect is so important in my film: we need to understand how the brain constructs that model of the world in our head.

“This is where storytelling and emotional engagement kick in.”

But the film’s most significant triumph lies in elevating the dialogue about how damaging fake news truly is. It explores its origins, consequences, and its insidious ability to manipulate human cognition.

Neuroscientist and Data Scientist Zahra Aghajan, an Assistant Professor at UCLA, explained how our brains interact with the virtual world.

She explains: “The virtual world, the online world, has become a new part of our identity.

“Now there is a virtual version of ourselves online where we don’t see real consequences of our actions.

“And that, in a sense, changes you, changes your knowledge tree within your neurons and within your brain.

“So, if somebody hacks the information feed, they hack the mind. Because these two are the same phenomenon with different appearances.”

Dr Aghajan highlighted the role of emotions in learning, with fear being the most powerful influence on what we recall.

She said: “Fearful images are the best ones to remember. It is very safe to say that stories that play on fear will stick with us the best and the longest.

“Conspiracy theories mostly play on fear, so once you engage the fear circuitry, that memory is there to stay.”

Dr Aghajan also explained how our brains engage in pattern recognition and completion.

She said: “Our brain is a master at pattern recognition. It makes stories and scenarios, even non-existent ones.

“When we get fearful information, it starts making all of these nasty scenarios that don’t even exist so that if one of them comes true, we won’t be surprised.

“And then, as soon as something happens that fits into one of those scenarios, our brain goes, ‘Aha, I was right’.

“So what happens when we stereotype? We recognise a pattern. So we put a person in a certain category and because that person belongs to a certain category, then we do pattern completion.

“So we allocate characteristics that that person might not even have.

“And finally, we do prediction because we would then predict that that person is going to do certain actions because they belong to that stereotype.

“So if we apply it to politics, let’s say that we think of someone as Republican or Democrat.

“So we already associate them with a certain stereotype and we already expect them to believe in certain things and act in certain things, even though that might not be true.

“And this is where a lot of the current polarisation is coming from.”

The Austrian Investigative journalist Michael Nikbakhsh, from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), was clear that the ability to hack the feed was regarded as very real by politicians attempting to ambush the narrative in a process he described as ‘message control.’

He explained how political actors can align media with their narratives through financial influence (“ad-corruption”) and offer exclusive access to information at exclusive meetings that shape narratives which are, to outsiders, completely invisible.

This phenomenon, he warned, leads to reporting by journalists who are embedded in the political system and amplifies political messages without scrutiny, with the inevitable result that it undermines the media’s role in a free society.

He said: “It creates a bubble. The responsibility of media can’t be to multiply political messages without contradiction.

“Journalism must not be a servant of those in power. Never. This turns journalism into public relations. Would we then still be an open, free society? No.”

Moser’s documentary makes clear the dangers of echo chambers—environments where struggling media organisations feed audiences only what reinforces their worldview, gradually weeding out inconvenient alternative voices, showing that it’s not just manipulative but also corrosive to democratic society.

American writer Susan Benesch, founder of the Dangerous Speech Project, explained: “Conspiracy theories work very well when they bounce back and forth in what we call echo chambers.

“When a group of people repeat the same false information to each other over and over inside a virtual space, that makes them feel as if there isn’t any other reality competing with that conspiracy theory.

“That is remarkably compelling for people, just like a real echo chamber is.”

She adds: “These online echo chambers don’t have physical walls, of course, but they have virtual, powerful walls that are built and reinforced by algorithms that feed people information that the algorithm thinks they want.

“In other words, whatever you are looking at, the algorithm gives you more of that, which is a way of echoing back to you what you’re already thinking and seeing and believing.”

Yet the industry does not even recognise this as a problem.

A recent ruling over a complaint I made to the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO) about one-sided coverage involving a Labour minister forced to resign in a scandal about a mobile phone stated: “The Editors’ Code of Practice does not address issues of bias.

“The press has the right to be partisan, to give its own opinion, and to campaign, as long as it takes care not to publish inaccurate, misleading, or distorted information.”

The documentary’s tagline, ‘If you can hack the information feed, you can hack the mind’, encapsulates its central thesis.

It claims in its PR material to offer a glimmer of hope in the potential for upgraded journalism and artificial intelligence technologies to act as modern “spam filters” for disinformation.

But what I’ve discovered is that the drastic underfunding of journalism and the inherent risks of AI being co-opted as a substitute for real news leaves little room for optimism.

To quote the film’s Professor Peter Cochrane, a British AI pioneer: “I don’t think people understand the value of truth.

“I don’t think they understand the actual capability of lies to destroy civilisation, to destroy lives.

“I perhaps have to wait until the situation gets more serious before people will actually start to take that seriously.”

Judging by the packed cinema where I watched the film at the Burg Kino in Vienna, there is significant concern about this issue.

I even heard the film’s central message in action as I left the cinema and overheard a couple discussing Zahra Aghajan’s deep insights into fake news as they walked down the main Ring Road encircling the city centre a few feet in front of me.

The young woman said: “I thought she was very good. Very interesting.”

Her companion replied, “Well, yes. But really, how seriously can you take someone who’s only an assistant professor?”

I couldn’t help thinking again of the words of the ‘assistant professor’ herself.

Hack the feed, and you hack the story, and no matter what you say, it won’t be believed anyway.

Michael Leidig is a British journalist based in Austria. He was the editor of Austria Today, and the founder or cofounder of Central European News (CEN), Journalism Without Borders, the media regulator QC, and the freelance journalism initiative the Fourth Estate Alliance respectively. He is the vice chairman for the National Association of Press Agencies and the owner of NewsX. Mike also provided a series of investigations that won the Paul Foot Award in 2006.

Friedrich Moser, born in Austria in 1969, transitioned from a career in journalism and television editing to filmmaking. He is known for his 2015 documentary A Good American, which examines how a National Security Agency (NSA) whistleblower exposed the abandonment of a surveillance program linked to the prevention of 9/11. Moser studied journalism and history at the University of Salzburg, developing the analytical and technical skills that informed his filmmaking career. His work often addresses political and societal changes in post-Cold War Europe and beyond.

Main image: Courtesy Markus Winkler/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

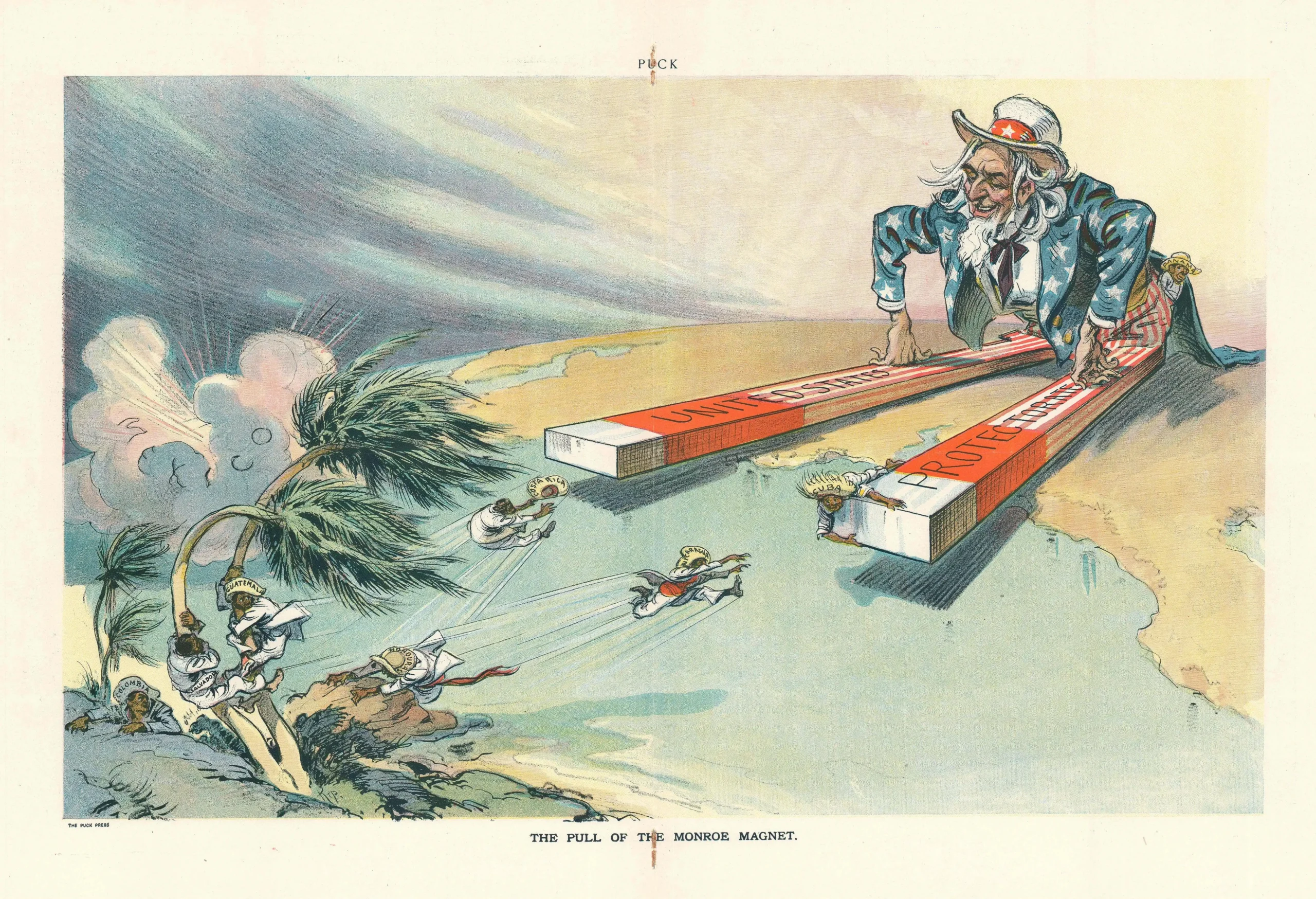

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting -

The fight for Greenland begins…again

The fight for Greenland begins…again