At the edge of Europe. A cruise gateway on the Russian frontier

Emma Strandberg

- Published

- Lifestyle

For most travellers, Kirkenes is simply the final port on Norway’s coastal voyage. Stay a little longer, though, and you’ll find king crab feasts, Cold War relics, reindeer roadblocks, and the most fascinating frontier town in Europe, finds Emma Strandberg

If you’ve ever taken a cruise up Norway’s stunning coastline, chances are you’ve heard of Kirkenes. This is the end point for Hurtigruten and Havila ships, the turnaround where passengers disembark after sailing through fjords, islands and Arctic ports. For many travellers it’s little more than a final stop. But this small town of 3,500 people has far greater significance than its role as a cruise terminal.

Kirkenes sits at 69 degrees north, 250 miles inside the Arctic Circle and well above the Canadian treeline. It lies closer to Russia and Finland than to Oslo, and only ten miles from the Russian border. Geography has made it both a frontier and a meeting point, where cultures and trade have long overlapped. Sami, Finnish, Russian and Norwegian families have lived here for generations, farming, fishing and mining to make a living.

Life here has always been defined by extremes. In summer, Kirkenes is bathed in midnight sun; in winter, it sinks into polar night. Thanks to the Gulf Stream, the Barents Sea stays ice-free year-round, keeping its harbour open even in the depths of January. This accessibility has made the town important for shipping and for people moving between East and West.

In recent decades, Kirkenes was best known for its open border with Russia. Shoppers, tourists and workers crossed daily, and traffic peaked at around 1,000 people a day. Locals saw themselves less as living on a fault line, more as a bridge between neighbours. That changed in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine. Now the Storskog crossing, once so busy, is heavily monitored. Border certificates have been cancelled, Visa and Mastercard no longer work in Russia, and trade has slowed to a trickle. Only 100 people reportedly crossed here in March this year. New fences have gone up, security drills are routine, and the Schengen border feels more solid than ever.

Kirkenes itself, however, is an inclusive and wholly welcoming place. Signs are still written in multiple languages, conversations are often overheard in Russian, and the town centre bursts with energy during festivals. Reindeer wander the roads, porpoises play in the fjord, and despite global tensions, the town remains rooted in neighbourliness.

At the same time, it has become a magnet for world attention. Summits and forums draw political leaders, military officers and researchers from across Europe, the US and Asia. The Arctic’s security, energy and future are all debated here, in a town that once sheltered underground from the most intense bombing campaign in Europe during the Second World War.

For visitors, this mix of rugged Arctic life, frontline geopolitics and warm hospitality makes Kirkenes a destination in its own right. It is a place where Europe ends and Russia begins, but also where travellers discover a resilient community, proud of its history and surprisingly keen to share it.

What to see and where (not) to ‘go’

Kirkenes is the kind of place that rewards the curious. Just 10 miles outside town you’ll find yourself at Storskog, the only open land crossing between Norway and Russia and, famously, Europe’s most closely watched border. Yes, you can take photographs, but the warning signs are almost comic: “no inappropriate gestures” towards Russia, including – believe it or not – “peeing”.

Drive a little further and you stumble into a Cold War time capsule. Skarferhullet, a border point closed since 1966, still bears its scars: a watchtower, now bristling with modern cameras; a rusting fence that disappears into the undergrowth; and twin boundary stones, yellow for Norway and red-and-green for Russia. The track once led pilgrims to a chapel founded in the 1500s by the Orthodox monk Trifon. Today the Boris Gleb church marks the same spot.

When the frontier was fixed in 1825, Russia clung to this small sliver of land west of the river, while Norway gained a larger stretch to the east. Standing here, the weight of history is tangible.

For those who prefer their curiosities with a quirk, Kirkenes also offers Treriksrøysa, a cairn where three time zones – Central European, Eastern European and Moscow Time – meet. It’s a three-hour drive and a three-mile hike, but if that sounds too ambitious, you’ll find a replica at the airport, proof that Kirkenes doesn’t take itself too seriously.

Back in town, the layers of history are just as visible. During the Second World War, Kirkenes was the most bombed town in Europe. By the final months of German occupation, 2,500 residents were living underground in a disused mine at Bjørnvatn. A memorial stone now marks the spot where children were born in the tunnel. Walk the streets today and you’ll see why the town looks the way it does; rows of plain, post-war blocks that speak less of design than survival.

Yet for all that weight of history, the town buzzes with energy. If you arrive during Kirkenes Day, the harbour transforms into a carnival of food trucks, live music and visitors pouring in from across Finnmark. One minute you’re dodging reindeer on the road, the next you’re watching porpoises arc through the fjord. Even the impounded Russian ship in the dry dock feels less like a political statement and more like another piece in Kirkenes’s eccentric jigsaw.

And then there’s sport. The Kirkenes Puckers, the local ice hockey team, are proof of Arctic grit. With no rink of their own, they train where they can, using their ingenuity, and have resorted to playing on the frozen surface of the disused quarry crater or a local playing field. Their motto? “Busting down borders.” Their story has even made it onto television, where their blend of underdog spirit and ingenuity has captured the nation’s imagination.

Where and what to eat and drink

Kirkenes isn’t Oslo or Tromso, but it has a food scene that reflects its character: hearty, unpretentious, and full of stories. If you happen to arrive during the summer festival, expect something closer to a street party than a small Arctic town: food trucks line the harbour serving everything from reindeer burgers to waffles, while the music keeps going until the small hours (not that the sun sets to mark the difference).

The star of the local table is king crab. These giants, hauled from the Barents Sea, are best enjoyed the simplest way: steamed and served with butter or lemon. Several restaurants specialise in them, some even offering “crab safaris” where you catch your own dinner from the fjord before it’s cooked for you.

If shellfish isn’t your thing, there’s plenty of traditional northern fare to try: reindeer stew with root vegetables, salmon pulled straight from the rivers, and thick fish soups that taste like they were designed to get you through a polar winter. Local cafés will set you up with strong coffee and pastries – cinnamon buns and skolebrød are favourites – while bars in town pour Arctic beers and aquavit, Norway’s herb-infused spirit that promises to keep the cold at bay.

The real joy of eating in Kirkenes is the mix of influences. A menu might sit comfortably between Sami game dishes, Finnish-style pancakes and Russian dumplings, just as you’ll hear Norwegian, Russian and Sami conversations around you. It’s a town where food is as much about connection as it is about calories.

Where to stay

Kirkenes doesn’t do frills, but it does do variety. Most visitors base themselves in harbour-side hotels, all just a five-minute walk from the centre, where you can watch the fjord from your window before strolling into town. They’re popular with cruise passengers and make a solid, comfortable base.

If you’re after something more memorable, book into the Snowhotel. Guests can choose between rooms carved entirely from ice or timber cabins tucked into the forest, both open year-round. Reindeer and huskies lounge outside like extras from a Nordic fairy tale, making the hotel one of Kirkenes’s biggest attractions.

There’s also the floating option. Emma stayed aboard the Havila Pollux, part of Havila’s new, eco-friendly coastal fleet. Cabins are sleek and sustainable, and the ship doubles as both hotel and transport, whisking you off on a cruise of a lifetime through some of Norway’s most remote scenery. If you’re planning to travel the coast, starting in Kirkenes makes logistical (and atmospheric) sense.

On a tighter budget? Guesthouses and no-frills motels do a steady trade, particularly among students, migrant workers and backpackers. Facilities are often basic, but the hosts are usually warm, full of stories, and happy to help you make the most of your time in town.

Getting here

Getting to the edge of Europe sounds dramatic (and it is) but Kirkenes is far more accessible than its Arctic coordinates suggest. If you’re flying, there are several direct services each day from Oslo to Kirkenes Airport. The journey takes just over two hours, and on descent you’ll spot the kind of scenery that reminds you how far north you’ve come: winding fjords, swathes of pine and birch, and mile after mile of treeless tundra.

The airport is only a short drive from town. En route, you’ll pass through rugged landscapes, see remnants of the extinct mining industry that once dominated the town, and, if lucky, spot reindeer and bear.

There’s also a once-daily bus from Murmansk, still running despite the geopolitical chill. Nicknamed “the last bus”, it costs €50 each way and remains a rare physical connection between Russia and the West — a route used by travellers and cross-border families alike. It stops at the airport, linking Kirkenes to a world that now feels far more distant than the map suggests.

But many visitors arrive by sea. Kirkenes marks the start (or end) of Norway’s famous coastal voyage — a cruise route that hugs the country’s dramatic shoreline through 34 ports, all the way down to Bergen. For decades, it’s been served by Hurtigruten, and more recently by Havila, which now operates a fleet of next-generation, eco-conscious ships.

Emma Strandberg is an acclaimed travel journalist, writer and photographer who lives on the rugged west coast of Sweden. Her wildly popular books have been described as “authentic” and “gripping” by the Daily Express, and as a “triumph of travel writing” by The Sun.

READ MORE: ‘I boarded the world’s most eco-friendly cruise ship in Norway‘. Norway’s fjords have long lured travellers with their glassy waters, jagged peaks, and fishing villages — but at what environmental cost? With the country pledging all ferry and coastal traffic will be emissions-free by 2030, photojournalist and bestselling travel writer Emma Strandberg sails with Havila Voyages to see if a cruise along the Norwegian coast can finally be guilt-free.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main Image: Norwegian Fjords: Sheer cli!s and mirror-like waters showcase the dramatic Arctic landscapes.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller (and it’s not what you think)

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller (and it’s not what you think) -

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways -

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus -

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism'

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism' -

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50 -

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom -

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living -

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius -

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj -

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic -

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream -

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day -

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life -

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split -

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic -

The bon hiver guide to Paris

The bon hiver guide to Paris -

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj -

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality -

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok -

The European road test: The Jeep Wrangler Rubicon

The European road test: The Jeep Wrangler Rubicon -

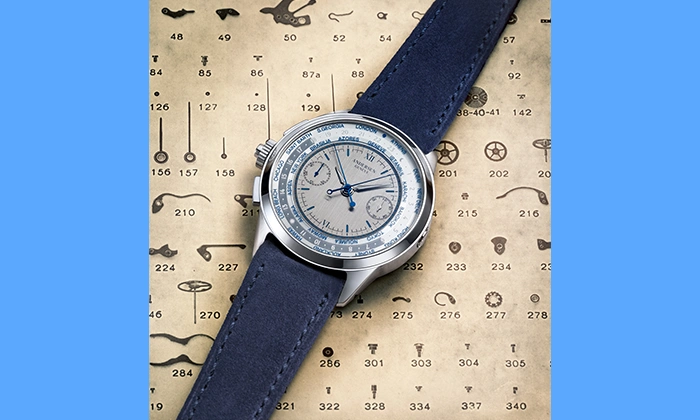

Rattrapante Mondiale – Split-Seconds Worldtimer

Rattrapante Mondiale – Split-Seconds Worldtimer -

Adaaran Select Meedhupparu & Prestige Water Villas: a Raa Atoll retreat

Adaaran Select Meedhupparu & Prestige Water Villas: a Raa Atoll retreat -

Heritance Aarah: an island escape crafted for exceptional family and couples’ stays

Heritance Aarah: an island escape crafted for exceptional family and couples’ stays -

Stanley Johnson in Botswana: a return to the wild heart of Southern Africa

Stanley Johnson in Botswana: a return to the wild heart of Southern Africa -

Germany’s Jewellery Museum in Pforzheim unveils landmark exhibition on dining culture

Germany’s Jewellery Museum in Pforzheim unveils landmark exhibition on dining culture