How financial accounting killed good management

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Banking & Finance, Global Economy, Home

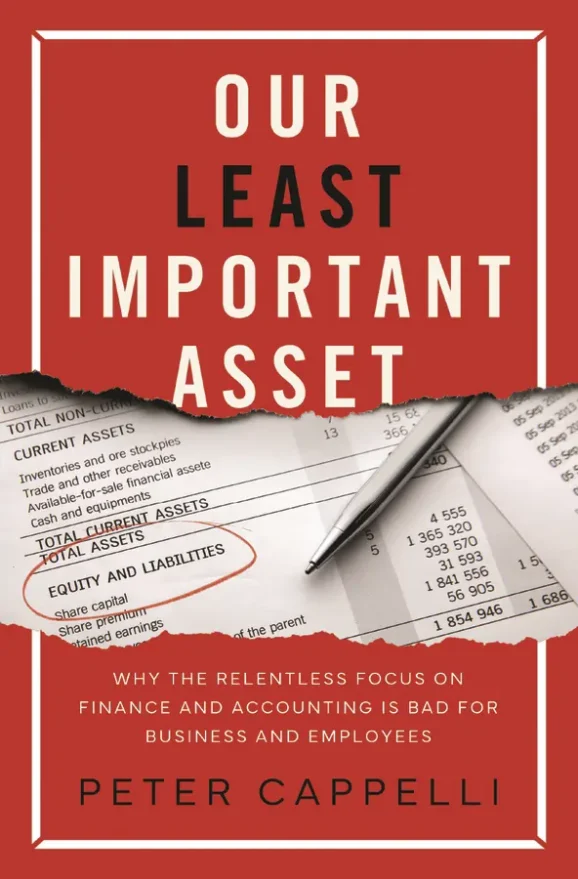

As modern corporate culture continues to be digitally transformed, financial accounting rules have turned many companies’ greatest asset into a liability, Wharton School’s Peter Cappelli tells Alex Katsomitros

In 2005, Sears, one of the largest US retailers, was acquired by ESL Investments, a hedge fund headed by Edward Lampert. Once a pioneer in worker empowerment that employed over 300,000 people, Sears switched to top-down management, with Lampert practically taking all decisions. A financier with no experience in retail, Lampert cut labour costs and invested much of the firm’s cash in stock buybacks, aiming to optimise financial performance. Eventually the retailer went bust in 2018, earning Lampert several mentions in “Worst CEO” lists.

Killing jobs

In his recent book Our Least Important Asset: Why the Relentless Focus on Finance and Accounting is Bad for Business and Employees, Peter Cappelli – who teaches management at the Wharton School – argues that Sears is emblematic of a deeper problem in modern corporate culture. The erosion in employee hiring and management practices can be attributed to an unlikely culprit: financial accounting – the branch of corporate accounting that covers financial transactions, including preparation of financial statements. Bizarrely enough, its rules dictate that money spent on employees is the worst corporate expenditure. Salaries are deemed fixed costs, even if employees can easily get sacked, while moving money to other categories makes companies more valuable in the stock market. Training is equally discouraged, although employees become a more valuable asset with experience, unlike physical assets. As Cappelli recalls in the book, one CEO told him that his job was to employ as few people as possible. Instead, a huge labour outsourcing industry has emerged, helping companies shift employee costs onto other categories – meaning that US corporations spend around 30% of their labour budget on non-employees, mainly “leased” ones. “A company could look like they’re super productive because they have relatively few employees,” Cappelli says from his office in Philadelphia. “Tech companies like Google have as many contractors as employees.”

Current critiques of corporate culture have focused on short-termism, often imposed by the need to maximise shareholder value. Cappelli goes against the grain, arguing that it’s financial accounting, the roadmap managers follow to raise value, that matters more. The question “Where have all the good jobs gone” is often answered with thorough analyses of globalisation’s impact on employment, but there’s rarely scrutiny of the decisions employers make, he explains. Not surprisingly, productivity has also stagnated. “Labour costs, particularly for frontline workers, have stayed so low that it hasn’t been a problem for employers to keep things the way they are, rather than invest in labour-saving technology, which is where productivity improvements could come from,” says Cappelli. Massive immigration hasn’t helped either. “A huge supply of workers from poor countries, mainly to our south, took over many of the unpleasant jobs, and that kept them unpleasant,” he argues. “If you look at the jobs where we have benefited from undocumented workers, technology hasn’t changed much.”

Currently, nearly all developed economies face acute labour shortages, but these are more a reflection of “pennywise and pound foolish” corporate culture that refuses to train employees, rather than demographic or macro-economic factors: “Economists are always looking outside the firm for explanations, never inside,” Cappelli says. One reason why employers can’t find the right applicants is that they are just too demanding, he argues. “Job requirements are stunningly specific, like five years of work experience with specific machine tools or even knowledge of particular customers.”

Financial accounting rules have also transformed business leadership. Salaries now make a small part of CEO remuneration, with leaders receiving stock options and other bonuses instead, registered as corporate expenses. Their background has also changed. After World War II, engineers replaced lawyers and bankers in boardrooms, bringing with them a mindset that focused on achieving measurable goals, a management method called “optimisation”. In the 1980s, finance became the preferred path to the C-Suite, with Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) gaining more power. More recently, the advent of data scientists reinforced the push to optimise financial results by cutting corners. What leaders don’t realise, Cappelli argues, is that minimising their staff indirectly raises costs elsewhere, while making it more difficult for firms to forge a mission for their employees.

MBAs, a major gateway to top jobs, reinforced these trends, although Cappelli, who teaches at one of America’s most prestigious business schools, hesitates to put the blame squarely on his profession. “Business education follows the business community, it doesn’t lead,” he says. However, he recognises that financial accounting dominates the field. “The problem with business schools is that we have different departments teaching different things,” he says. “My classes focus on understanding people as humans, but in other classes they are thinking about how you could design systems that minimise humans. The loudest voices reflect what employers want.”

Taylorism 2.0

If one expects technological progress to make things better for workers, they are in for massive disappointment, Cappelli believes. In fact, it has turned the clock back a century ago when the engineer and management guru Frederick Taylor reduced employees to clogs in a giant machine through his scientific management theory. Today, this machine isn’t a grinding wheel like the one Charlie Chaplin’s character is trapped into in Modern Times, but artificial intelligence (AI) software, increasingly popular among business leaders due to its labour-cutting potential. Moving decision-making from supervisors to AI, Cappelli argues, reduces worker empowerment, as algorithms increasingly decide assignments, schedules, performance monitoring and job design, with data scientists taking the place of Taylor’s engineers. Even modern practices promising to empower workers, like agile and lean management, have been redefined to serve this AI-driven push for optimisation.

One particular area where AI promises to cut costs is recruitment, with thousands of vendors advertising allegedly groundbreaking AI-powered hiring solutions. However, few are really worth it, Cappelli argues, since their models require amounts of data that few employers have. “AI could be very good, perhaps better than employees, at hiring. But that’s not happening, because it requires a lot of upfront investment,” he says, adding: “If there are any biases in the AI system, like gender or race biases, they are transparent to anybody, so you could get sued. Now it’s hard to sue employers, you can’t document how they make hiring decisions because they’re so disorganised.” One example is an algorithm Amazon created to replace recruiters. Eventually, the company was forced to abandon it due to its bias against female applicants.

Monitoring employees has also become a science in itself, with wearable technologies feeding algorithms with data on what employees do, even after work. Wellness programmes that track employee fitness down to serum cholesterol levels have practically become compulsory at many companies in a bid to cut healthcare costs. So why don’t workers push back? “Some union initiatives are about this, for example at Amazon warehouses. But in the US, it’s almost impossible to get a union if your employers are willing to fight it,” Cappelli explains. “It’s pretty easy to fight employees, so they can’t push back on that dimension.”

HR to the rescue

If workers can’t resist, professional recruiters could at least try. In the book, Cappelli makes a plea for more robust HR departments. In 1980, a typical company had one HR staff member for every 100 employees; by 2020, it was roughly one for 150. As a result, hiring is increasingly delegated to line managers. “It’s inefficient because line managers are more expensive than recruiters, they don’t have time to figure out how to get good at this and we don’t train them,” Cappelli says. “But it looks better on financial accounting because you’re cutting headcount.” One consequence is that internal hiring and training have sharply declined, while a disproportionate percentage of candidates are recruited through personal connections and the time needed to fill vacancies has increased. HR staff should stop pandering to the C-suite and push back, according to Cappelli. “What the CEO hears is almost always what the CFO says, and the CFO only sees financial accounting numbers, so they don’t know what employee turnover costs are,” he says. “HR departments should be pointing out to the C-suite what the costs are with the current approaches.” The pandemic laid bare these hidden costs. When lockdowns started, employers placed many employees on furlough, but soon started laying them off due to uncertainty, only to complain about labour shortages when the economy opened up. The airline industry exemplified this trend, with most airlines facing significant recruitment bottlenecks, as they were trying to hire from the same talent pool.

More transparency

Can this decline in employee management and recruitment stop? Cappelli suggests that investors could push for more transparency, given that in an AI-driven economy, human work may be more valuable than ever. Alternative accounting systems to assess the value of labour already exist, but have not been widely adopted yet. Public information is scarce, with little consistency and depth in reporting. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has issued a requirement for companies to disclose human capital resources, but it’s up to companies to decide what to report, while few of them respond to relevant questions from shareholders.

Reporting a few metrics like employee turnover, voluntary quits, layoffs, labour and training spending, internally filled vacancies, and leased workers could help investors assess company values. One movement pushing in that direction is the Workforce Disclosure Initiative; its members – investors controlling assets worth $8tn – are putting pressure on large companies to report human capital data. “The reason is not particularly socially oriented. They want to make more money, and they can’t do it because they can’t value these companies,” Cappelli argues, whereas he thinks that we should be more worried about the bad decisions these companies make due to financial accounting rules and their impact on employees. But either way, more transparency would help. “Companies know those numbers. This is not an incredibly complicated exercise,” he says. “Making them report metrics wouldn’t be the perfect solution, but it would be a start.”

About Peter Cappelli

Peter Cappelli is the George W. Taylor Professor of Management at The Wharton School and Director of Wharton’s Center for Human Resources. He is a regular contributor to ‘The Wall Street Journal’ and writes a monthly column for ‘HR Executive’ magazine. His recent work on performance management, agile systems, hiring practices, and other workplace topics appears in the ‘Harvard Business Review’.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Managing cross-border risks in B2B e-commerce

Managing cross-border risks in B2B e-commerce -

J.P. Morgan launches first tokenised money market fund on public blockchain

J.P. Morgan launches first tokenised money market fund on public blockchain -

Aberdeen agrees to take over management of £1.5bn in closed-end funds from MFS

Aberdeen agrees to take over management of £1.5bn in closed-end funds from MFS -

Enterprise asset management market forecast to more than double by 2035

Enterprise asset management market forecast to more than double by 2035 -

EU Chamber records highest number of entries for 2025 China Sustainable Business Awards

EU Chamber records highest number of entries for 2025 China Sustainable Business Awards -

Inside Liechtenstein’s strategy for a tighter, more demanding financial era

Inside Liechtenstein’s strategy for a tighter, more demanding financial era -

‘Stability, scale and strategy’: Christoph Reich on Liechtenstein’s evolving financial centre

‘Stability, scale and strategy’: Christoph Reich on Liechtenstein’s evolving financial centre -

Bridging tradition and transformation: Brigitte Haas on leading Liechtenstein into a new era

Bridging tradition and transformation: Brigitte Haas on leading Liechtenstein into a new era -

Liechtenstein in the Spotlight

Liechtenstein in the Spotlight -

Fiduciary responsibility in the balance between stability and global dynamics

Fiduciary responsibility in the balance between stability and global dynamics -

Neue Bank’s CEO on stability, discipline and long-term private banking

Neue Bank’s CEO on stability, discipline and long-term private banking -

Research highlights rise of 'solopreneurs' as technology reshapes small business ownership

Research highlights rise of 'solopreneurs' as technology reshapes small business ownership -

Philipp Kieber on legacy, leadership and continuity at Interadvice Anstalt

Philipp Kieber on legacy, leadership and continuity at Interadvice Anstalt -

Building global-ready funds: how South African managers are scaling through offshore platforms

Building global-ready funds: how South African managers are scaling through offshore platforms -

Global billionaire wealth hits record as relocation and inheritance accelerate, UBS finds

Global billionaire wealth hits record as relocation and inheritance accelerate, UBS finds -

Human resources at the centre of organisational transformation

Human resources at the centre of organisational transformation -

Liechtenstein lands AAA rating again as PM hails “exceptional stability”

Liechtenstein lands AAA rating again as PM hails “exceptional stability” -

Lusaka Securities Exchange surges ahead on reform momentum

Lusaka Securities Exchange surges ahead on reform momentum -

PROMEA leads with ESG, technology and trust in a changing Swiss market

PROMEA leads with ESG, technology and trust in a changing Swiss market -

Why collective action matters for pensions and the planet

Why collective action matters for pensions and the planet -

Structuring success with Moore Stephens Jersey

Structuring success with Moore Stephens Jersey -

PIM Capital sets new standards in cross-jurisdiction fund solutions

PIM Capital sets new standards in cross-jurisdiction fund solutions -

Innovation, advisory and growth: Banchile Inversiones in 2024

Innovation, advisory and growth: Banchile Inversiones in 2024 -

Digitalization, financial inclusion, and a new era of banking services: Uzbekistan’s road to WTO membership

Digitalization, financial inclusion, and a new era of banking services: Uzbekistan’s road to WTO membership -

Fermi America secures $350m in financing led by Macquarie Group

Fermi America secures $350m in financing led by Macquarie Group