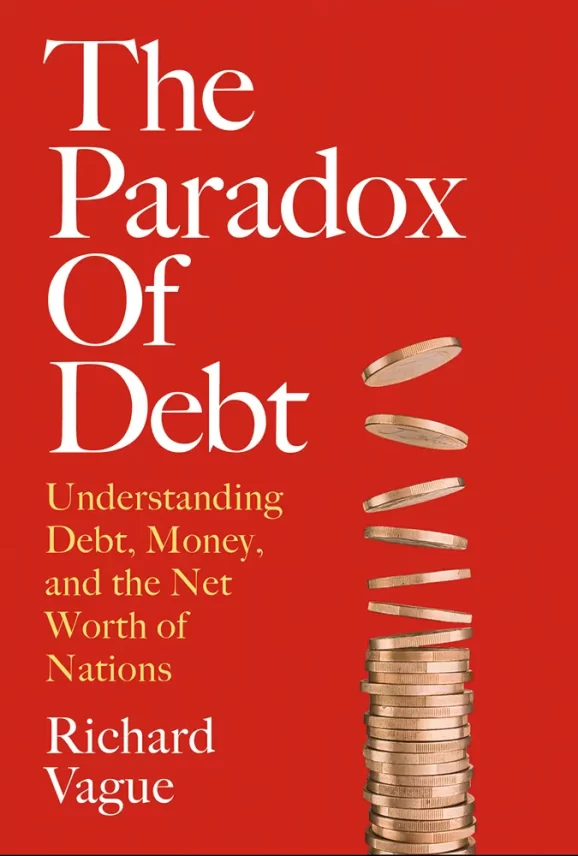

Investor and entrepreneur Richard Vague uses history to underline the misconceptions surrounding government debt, and highlights why the UK government must do more to seize upon areas of the economy that are ripe for investment

There is no doubt that the UK’s elected officials, policymakers, and business executives would benefit from a deeper understanding of debt in the British economy. What is widely misunderstood is that increased government debt increases household wealth. Government money does not disappear when it is spent. Instead, it largely goes into the accounts of households, directly through salaries and other payments and indirectly through the salaries of those who work for vendors of the government. It’s a simple matter of accounting. By definition, income has to equal expense in any economy, someone’s expense is always someone else’s income, and the expense of the government most often ends up as income to households.

In fact, during the three years of the pandemic, 2020 to 2022, UK government debt increased by £602bn, but household wealth increased by a much greater amount, an estimated £1.7tn. That increase came from government spending and payments to households, plus the increase in the value of stocks and real estate that came from the flood of increased pandemic-era government debt and spending.

In total, household wealth in the UK, at £12.6tn, towers over the £2.5tn in government debt. Critics lament that the British will never be able to pay off that government debt, nor will their children or grandchildren. But households already own assets well in excess of that level, and in fact, they hold much of that UK government debt itself as an asset.

But doesn’t excessive government debt cause inflation? No. For developed economies, there is no compelling evidence that it does. There was no inflation in major Western economies after the massive government debt growth that followed the global financial crisis in 2007-08, nor in Japan after the massive government debt growth that followed its 1998 crisis. In fact, since World War II, for the 47 largest countries in the world where we have sufficient data, there were 85 instances of very high government debt growth, but only 17 were followed by high inflation. And we had a number of bouts of inflation that were not preceded by this high government debt growth.

There is also a similar lack of evidence that high money supply growth, which is a very different phenomenon to high government debt growth, brings inflation. The notorious 1970s bout of inflation that bewitched a generation of economists, and which has come to define the conventional view of inflation, lasted from 1973 to 1982. This inflation was largely a function of high oil prices, which came as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) strangled oil production in retaliation for the western support of Israel in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The Iranian Revolution in 1979 further disrupted oil production. These events drove the price of oil from $3.50 to $39.50 per barrel, a tenfold increase that pushed US inflation to a peak of 14.6% in 1980. It’s as if today’s price of oil were $800 per barrel instead of $80. This inflation was vanquished not by high interest rates, as many believe, but by US domestic oil price deregulation, which allowed domestic producers to sell their oil at over $30 per barrel instead of the regulated price of $6 to $15. With that enhanced profit opportunity, the domestic industry scrambled to discover new oil fields, with the number of oil and gas drilling rigs rising 139%, from 1,658 rigs in 1977 to 3,970 rigs in 1981. As a result of all this new drilling, North American oil production jumped from 12.2 million barrels per day in the late 1970s to 15.3 million barrels per day by 1984. Predictably, the surge in production brought down the price of oil, to $12 per barrel by 1986 – and this sent inflation tumbling to 2% (the tumbling price of oil also left a lot of bankrupt drillers in its wake). Infamously, however, central bankers, following the influential economist Milton Friedman, believed the period’s inflation had been more a product of the country’s money supply than the growth in oil prices, and so in 1979 hiked interest rates, precipitating a major recession.

The lessons of Liz’s blunder

But what about the financial scare that came from the Liz Truss tax cut? Isn’t that proof of the dangers of high government debt? That debacle had more to do the with the weak pound and gnawing trade deficit than the size of the government’s debt. Liz Truss was attempting to emulate her icon Margaret Thatcher in cutting taxes to stimulate a rebound, but the economic circumstances surrounding the Truss cut were vastly different than those surrounding Thatcher.

Most importantly, Thatcher had a 2% trade surplus that contrasted markedly with Truss’s problematic 3.5% trade deficit, a deficit exacerbated by the difficulty of Brexit, and which looks to get worse with Ukraine-war-related energy prices. This adds to downward pressure on the currency, bringing higher import expenses and inflation and upward pressure on interest rates. A trade deficit is one of the most important factors in any economy, and the UK’s unfavourable position here could mean years of higher prices for UK consumers.

Thatcher had other key advantages as well, most notably low private debt levels, which meant that the private sector had ample room to grow through increased spending on investment. For Thatcher, the ratio of private debt to GDP was a very low 56% to GDP, while for Truss it was almost triple that level at 150%.

Notably, Thatcher also had smaller budget deficit, although as we have said, government deficits are not an adverse factor here. In fact, Japan’s current government debt total 242% of GDP has been accompanied by comparatively mild inflation, though it far exceeds the UK government debt level of 101% of GDP.

And there’s another key piece of information here: Truss, along with many economists, wrongly believed it was Thatcher’s tax cuts that brought the economic growth of the 1980s. Instead, it was a £31 a year surge in private debt lending that brought £33bn a year in nominal GDP growth during the first half of the 1980s. Thatcher actually increased taxes during the first part her tenure, though she cut the top rate of the income tax, and cut spending, though only slightly.

The 1980s are remembered as a boom time, the era of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. But the key factor was a prolonged private sector lending boom that, as all private debt booms do, brought euphoria in its initial years. In Britain, private debt to GDP (the combination of business and household debt) was an ultra-low 58% in 1980, shortly after Thatcher’s ascension to prime minister, and exploded, more than doubling to 115% by 1990. It was one of the most rapid escalations of private sector debt in Western economic history. There was almost as big of a lending boom in the US. In both cases, a disproportionate amount of this was real-estate related debt, bringing a spree of construction that – as is typical – reduced unemployment and flooded the economy with money.

But overlending usually brings an economic hangover, and these certainly did. Thatcher stepped down as Prime Minister in 1990 just as the troubles began. Too many buildings had been built, business had overexpanded beyond the level justified by demand – and those real estate loans started going bad, construction companies announced layoffs, and banks and other lenders started to fail. In the UK, Thatcher’s successor, John Major, inherited the brunt of this, with a recession in 1990 and 1991, and unemployment rising from 6.8% in 1990 to 10.4% in 1993.

Notably, the real GDP growth of 3% in the 1970s in the UK was higher than the 2.7% growth of the 1980s even with that lending boom.

Beyond the misconceptions of government debt

Policymakers and business leaders should look through the misconceptions surrounding government debt and recognise that its growth can bring household wealth, and does not lead to inflation. Government debt growth is not without issues, however, the primary among them being that it leads to higher levels of inequality. But that is another (very important) topic for another day.

In the meantime, there is room for a strategic increase in key areas of the British government’s budget, and there are any number of areas that are ripe with opportunity and could readily boost the UK’s growth and the business environment – from worker training to green energy and infrastructure spending and more. Britain should look to take advantage of that opportunity.

About the Author

Richard Vague is the author of new book ‘The Paradox of Debt – A New Path to Prosperity Without Crisis’, he is an investor and entrepreneur. He has served as the Secretary of Banking and Securities for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and co-founded two US banks – First USA, which was sold to Bank One and Juniper, which was sold to Barclays.