Britain’s most storied guidebook series returns with a Derbyshire volume that mixes celebration with stark warnings of industrial devastation

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Lifestyle

As navigation apps chase speed and efficiency, the new Heritage Shell Guide to Derbyshire restores depth and perspective, revealing the county’s beauty and scars with a voice as distinctive as its landscapes, finds John E. Kaye

When John Betjeman launched the first Shell Guide in 1934 with his now-famous Cornwall, he set in motion a series that would become one of the most distinctive publishing projects of twentieth-century Britain. Sponsored initially by Shell to serve the new motoring public, the Guides were never mere handbooks to churches and inns but important works of judgement and personality, written by poets, painters and critics whose voice and perspective mattered as much as the information they conveyed. What began as a motorist’s companion soon turned into a cultural phenomenon, drawing into its orbit figures such as John Piper, Stephen Bone and Henry Thorold, each producing volumes that mingled scholarship with eccentricity, anecdote with opinion, and history with humour. The result was a body of work that captured the spirit of place more vividly than any conventional gazetteer.

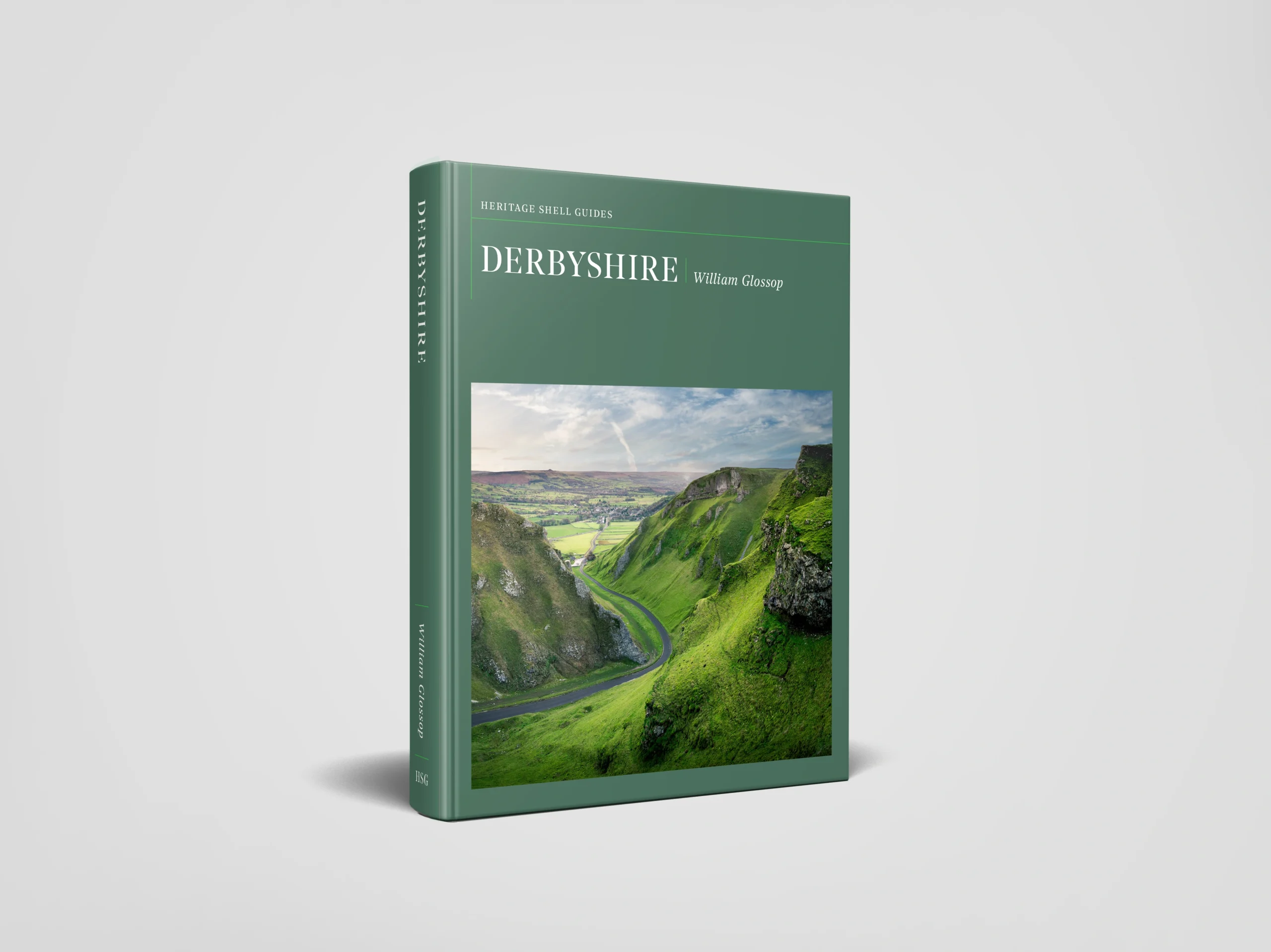

The Heritage Shell Guide Trust has in recent years sought to revive that tradition, commissioning new volumes for counties across England and Wales while maintaining the qualities that defined the originals. William Glossop’s Derbyshire, newly published in 2025, is an exemplary addition to this line. It is both a continuation and an updating of Thorold’s earlier Derbyshire guide, expanding the coverage, sharpening the focus, and ensuring that the distinctive voice of the author is never lost in the detail.

Glossop is steeped in his subject and writes with the intimacy of someone who has walked, camped and researched the county for decades, carrying forward Thorold’s enthusiasm for architecture and landscape while adding his own blend of candour and concern.

The book opens with an expansive introduction that moves from prehistoric cave art at Creswell Crags through the Roman exploitation of lead to the splendours of Haddon, Hardwick and Chatsworth. It is a county history told through its buildings and landscapes, and Glossop never shies away from difficult truths. He writes with evident admiration of the Peak District National Park and of the preservation of great houses and churches, but he also points to scars on the landscape: the ravaged quarries of Great Rocks Dale, the despoliation of coalfields around Swadlincote, and the uneasy legacy of industrialisation. His frankness recalls the tradition of Shell authors who combined celebration with critique, and it gives this volume an honesty that lifts it above the blandness of most modern county guides.

The heart of the book lies in its gazetteer, running to more than three hundred pages, which moves systematically through the towns and villages of Derbyshire. Each entry is underpinned by research and enlivened through personal observation. Rather than fall back on the cheap stock phrases that fill so many guidebooks, Glossop brings out the character of each place with detail and eloquence, showing its buildings, landscapes and history in a way that feels both knowledgeable and personal.

Ashbourne, for instance, is frequently described as a handsome market town with a photogenic square, a scattering of antique shops and the promise of a cream tea. Glossop, on the other hand, refers it a place of real architectural distinction, anchored by St Oswald’s church, which George Eliot once praised as the finest parish church in England, and enriched by Georgian houses, historic almshouses and layers of history.

Chesterfield, often dismissed as a former mining town, is here reclaimed as a “real-life Cinderella” whose Art Deco town hall and vast open market deserve attention. Bakewell, meanwhile, is seen not just as the tourist’s destination for pudding but as a town layered with Saxon, Norman, medieval, Georgian and Victorian history, anchored by its great church and enriched by a dense mix of houses, halls and civic buildings.

Throughout, Glossop marks “must-see” places with stars, while always allowing space for lesser-known gems such as Somersal Herbert Hall or the Crispin Inn at Ashover. Glossop, a former barrister and judge, pulls no punches when it comes to how commercial pressures continue to shape and scar the county’s landscape. His guide issues an unusually stark warning about the scale of quarrying, which he condemns as a blight on its historic landscape.

Vast areas of the county bear the scars of industrial extraction, with hills hollowed out at Earl Sterndale, valleys flooded by abandoned pits, and other vistas left irreparably altered, he writes. Parts of the county are, he says, “a scene of wholesale devastation”, and “an unremarked disgrace about which environmental campaigners have strangely been silent.” Great Rocks Dale near Buxton has been blasted into what he calls “an Armageddon”.

Glossop’s warts ’n all take on Derbyshire shows why the Heritage Shell Guides still have a place alongside apps and satnavs. Google Maps might be quicker at getting you across the county, but it will never tell you why a church tower leans, how a market town grew, or what a ruin once meant to those who built it.

The Heritage Shell Guide to Derbyshire by William Glossop will be published in paperback on 1 November 2025. The richly illustrated volume features more than 500 photographs and artworks — an unusually comprehensive visual record for a county guide — and is available from Waterstones priced at £25.

READ MORE: ‘Portugal’s GR22 crowned Europe’s most rewarding hiking trail‘. A 584km route across Portugal has topped a new ranking of Europe’s hiking trails, scoring 98.59 out of 100 after researchers compared difficulty, length, elevation, sunshine and accommodation with rivals in Switzerland, Greece, Spain and beyond.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main Image: The ruins of Peveril Castle, perched high above Castleton, are among Derbyshire’s most evocative landmarks and a reminder of the county’s long history set against the drama of the Peak District. © Supplied/iStock

Sign up to The European Newsletter

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Book Review: A history of the world told by animals — and it changes everything

Book Review: A history of the world told by animals — and it changes everything -

Make a list, check it twice: expert tips for running Christmas in hospitality

Make a list, check it twice: expert tips for running Christmas in hospitality -

December night sky guide: what to look for and where to find it

December night sky guide: what to look for and where to find it -

Four Seasons Yachts reveals overhauled 2027 Mediterranean programme

Four Seasons Yachts reveals overhauled 2027 Mediterranean programme -

The European road test: MG’s new electric flagships, the Cyberster and IM5

The European road test: MG’s new electric flagships, the Cyberster and IM5 -

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future -

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation -

We ditched Cornwall for North Norfolk — and found a coast Britain forgot

We ditched Cornwall for North Norfolk — and found a coast Britain forgot -

How BGG became the powerhouse behind some of the world’s biggest wellness brands

How BGG became the powerhouse behind some of the world’s biggest wellness brands -

Exploring France’s wildest delta: Julian Doyle on the trail of white horses, black bulls and the hidden history of the Camargue

Exploring France’s wildest delta: Julian Doyle on the trail of white horses, black bulls and the hidden history of the Camargue -

“Embarrassment is killing men”: leading cancer expert warns stigma hides deadly truth about male breast cancer

“Embarrassment is killing men”: leading cancer expert warns stigma hides deadly truth about male breast cancer -

Diving into… Key West, Florida

Diving into… Key West, Florida -

Nick Mason leads celebrity line-up at London Motor Week

Nick Mason leads celebrity line-up at London Motor Week -

The simple checks every man should do for breast cancer

The simple checks every man should do for breast cancer -

Concerto Copenhagen marks Danish EU presidency with gala at Bozar

Concerto Copenhagen marks Danish EU presidency with gala at Bozar -

What effective addiction treatment looks like today

What effective addiction treatment looks like today -

NOMOS Glashütte named Germany’s best sports watch brand 2025

NOMOS Glashütte named Germany’s best sports watch brand 2025 -

Stars, supermoons and shooting fireballs: why November’s sky is unmissable

Stars, supermoons and shooting fireballs: why November’s sky is unmissable -

“Derbyshire is both a treasure and a responsibility” — William Glossop on the New Heritage Shell Guide

“Derbyshire is both a treasure and a responsibility” — William Glossop on the New Heritage Shell Guide -

Inside the Maldives’ most exclusive getaway

Inside the Maldives’ most exclusive getaway -

Tripadvisor says this is one of the best hotels on Earth — we went to see for ourselves

Tripadvisor says this is one of the best hotels on Earth — we went to see for ourselves -

Britain’s most storied guidebook series returns with a Derbyshire volume that mixes celebration with stark warnings of industrial devastation

Britain’s most storied guidebook series returns with a Derbyshire volume that mixes celebration with stark warnings of industrial devastation -

Michelin shortlists Croatia’s Villa Nai 3.3 as one of the world’s best-designed hotels

Michelin shortlists Croatia’s Villa Nai 3.3 as one of the world’s best-designed hotels -

Drive your own safari: why Kruger is Africa’s most accessible wildlife park

Drive your own safari: why Kruger is Africa’s most accessible wildlife park -

Oggy Boytchev on Sardinia, an island of contrasts

Oggy Boytchev on Sardinia, an island of contrasts