The real AI challenge is human, not technical

Dr. Sarah Chardonnens

- Published

- Science

As businesses rush to implement AI tools, they risk overlooking the most critical component: the human brain. Without cognitive alignment and a deeper understanding of how people learn, automation can do more harm than good, warns Dr Sarah Chardonnens

I was in a strategy meeting with a large organisation recently when someone asked me a question I’ve heard more than once: “We’ve got the AI systems in place—why aren’t our teams making better decisions?”

It’s a question that speaks to a bigger issue. Businesses are racing to adopt artificial intelligence, layering algorithms across HR, logistics, finance, and product design. The tools are getting faster, more integrated, and more powerful. But beneath the surface, something is quietly going wrong: people don’t know how to work with them.

The problem isn’t a lack of technology but rather of cognitive readiness. We’ve rolled out automation faster than we’ve equipped people to think critically, reflectively, or independently in response to it. And in doing so, we’ve created environments where decision-making is often passive, rushed, or unexamined.

“What’s missing is not functionality. What’s missing is fluency.”

I come from a background in cognitive science and educational research, and I’ve spent over a decade studying how people learn, adapt and self-regulate. What I’ve seen, time and again, is that digital transformation strategies rarely account for how the human brain actually works. There’s a tendency to treat AI as plug-and-play, when what’s really needed is a redesign of how people engage with information, decisions, and uncertainty.

The Risk of Passive Compliance

In one reported case, a logistics company implemented an AI system that reassigned tasks based on behavioural data. The initial results showed improved efficiency, but soon after, signs of disengagement and talent drain began to emerge. No one could explain the logic behind the system’s decisions. Employees felt alienated, deskilled. Some stopped asking questions altogether.

This is a familiar pattern. And it points to something deeper than performance metrics. When people don’t understand how or why a system behaves the way it does, they begin to second-guess themselves—or, worse still, stop engaging altogether.

AI doesn’t cause that. Poorly implemented AI does. More specifically, AI that’s introduced without pedagogical grounding—without helping people build the mental frameworks they need to work with it intelligently.

When I talk to leadership teams, I try to shift the conversation. It’s not only about how the system works but also about how people respond to it. How they think through it. How they question it—or don’t. This isn’t technical training, then, but rather cognitive development.

Building Cognitive Fluency with the SYNAPSE Model

The real gap isn’t in the functionality of the tools themselves, but in the fluency with which people use them.

Fluency in this sense means competence and confidence. It means being able to interrogate an AI-generated recommendation, to understand the logic that underpins it, and to make an informed decision about whether to follow it. That requires more than training in tools. It requires training in thinking.

“What’s missing isn’t a tool. It’s the ability to think critically alongside it.”

Many organisations invest in toolkits, onboarding modules, and webinars, but these often stop at surface-level competence. They teach people how to use tools, but not how to think with them. That’s where the risks start to show. Decisions get made uncritically. Biases creep in unnoticed. Teams defer to the system rather than engage with it.

Therefore, this is more of a thinking gap than a skills gap. And it leads to what I call cognitive disengagement: a state in which people no longer feel responsible for the outcomes of their work, because they believe the system is making the decisions.

The good news is that this can be addressed. Cognitive alignment is not abstract or theoretical. With the right cognitive frameworks, there is strong potential to help people better understand what intelligent systems are doing, and how they can stay in control of their own judgement.

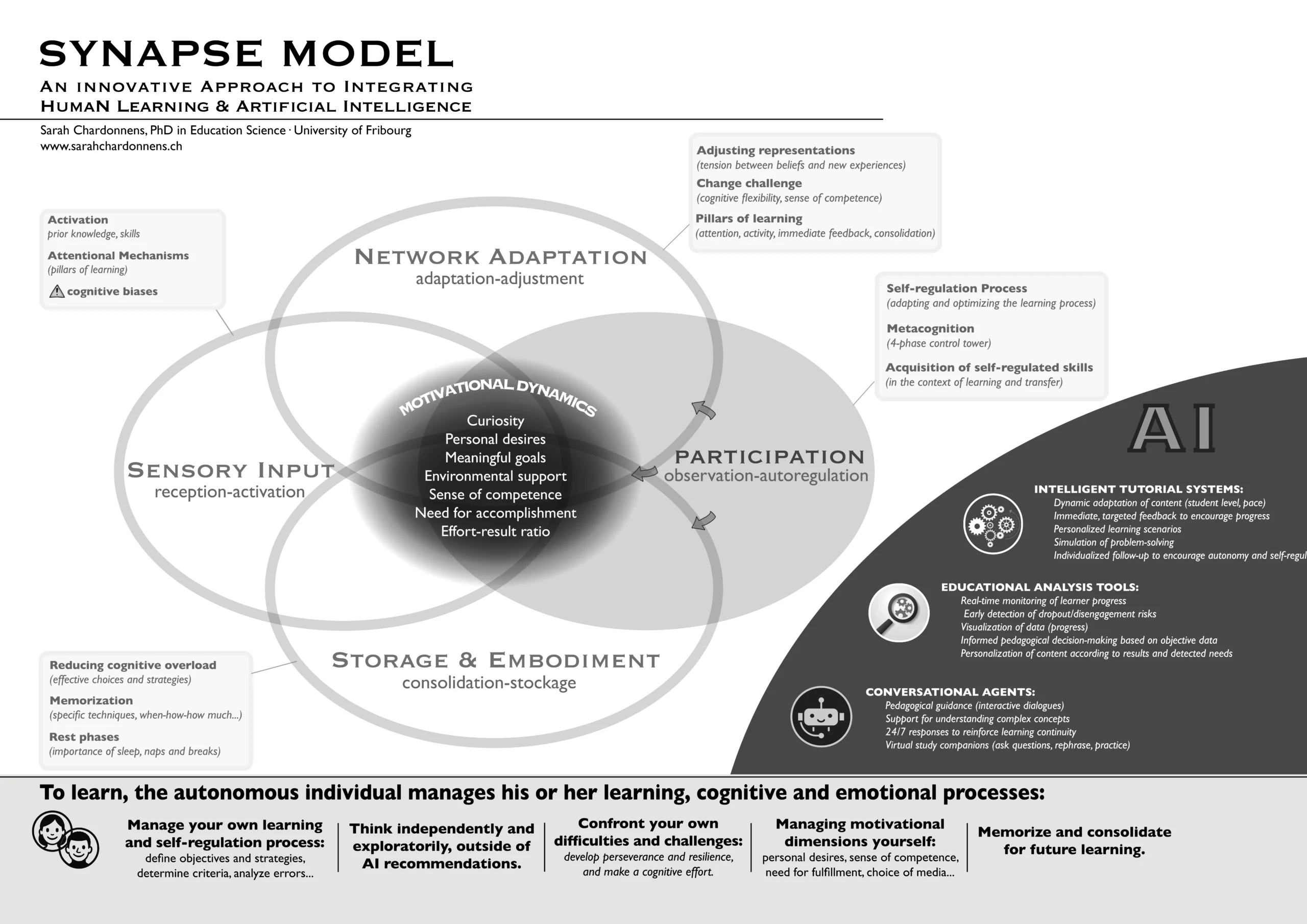

Drawing on approximately 400 scientific studies, I have conceptualised a cognitive framework called SYNAPSE—a way of understanding how we learn, and what the benefits and risks of AI are at each stage of that process. It’s not a training programme or a user manual, but a model for making sense of learning itself.

The model is based on four layers: attention and activation, internal adjustment, reflective self-regulation, and memory consolidation. These are based on foundational work in neuroscience and educational psychology, including the insights of French neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene, whose research on the brain’s learning cycles has influenced how we think about engagement, feedback and memory; Olivier Houdé, a specialist in cognitive inhibition and the ability to override impulsive responses with reflective thinking; and Barry Zimmerman, whose work on self-regulated learning remains critical to understanding autonomy in complex environments.

These four layers are not rigid steps, but dynamic processes. In real-world settings, they overlap and influence each other constantly. For example, if a user doesn’t feel emotionally safe or confident at the first stage—attention and activation—they may never engage fully with the task. Similarly, without time to reflect and regulate their learning, even a technically successful AI interaction can fail to result in durable knowledge or skill.

I don’t always explain it that way in a boardroom. But I do talk about the need to pace feedback, to give people space to test their own thinking, to structure moments of reflection—and to avoid overwhelming the brain with constant prompts and automation.

Making It Work on the Ground

What’s powerful is that these ideas don’t just belong in theory. While we don’t yet have definitive scientific data on real-world implementation, the SYNAPSE model offers a promising way forward. In my lectures and research, I’ve explored how it could be applied to adaptive learning platforms and corporate training environments—where content might be broken into manageable sequences, key ideas reinforced through repetition, and space allowed for reflection, in line with natural cognitive rhythms. Some colleagues are beginning to explore these applications, and the early interest suggests meaningful potential for improving how AI is integrated into learning processes.

“If your AI system removes friction, but also removes thinking, it’s not helping.”

I’ve seen the difference when organisations begin to think this way. One global firm I worked with rebuilt its onboarding around cognitive milestones rather than product walkthroughs. Instead of measuring speed, they measured retention. Instead of automating corrections, they prompted reflection. Not only did performance improve but the team reported feeling more confident and in control, too.

I’ve also worked with leadership teams in health and finance, where the stakes are higher and the complexity of information even greater. What they needed wasn’t another technical demo—it was a way to help their people build the mental stamina and self-regulatory skills to keep engaging thoughtfully with tools that operate faster than intuition.

In both cases, the shift comes from putting the brain back into the strategy—an approach I advocate through research and ongoing discussion with leaders and teams.

Embedding Human Learning in Tech Strategy

That’s a question more organisations need to ask. Too often, decision-makers assume that as long as a system is technically sound, it will be used intelligently. But that’s not how human learning works. Without reflective scaffolding, most users will fall back on instinct—or worse, compliance. They will trust outputs without analysis, follow instructions without context, and adopt tools without really understanding them.

The lesson is simple: digital tools are only as good as the minds that use them.

Too many organisations are over-equipped technically and underprepared cognitively. That imbalance creates real risks: poor decisions, disengagement, and a workforce that’s good at compliance but bad at adaptation.

Other researchers and policy bodies have drawn attention to this gap. For example, the OECD has called for greater focus on the cognitive skills needed to use AI effectively in the workplace, while UNESCO’s education strategy increasingly emphasises self-regulated, human-centred learning in the digital age. These findings echo what I see daily: that the success of AI hinges on whether humans can think critically in tandem with machines.

“The success of AI hinges on whether humans can think critically in tandem with machines.”

And this challenge is only going to grow. As large language models and generative AI tools become more integrated into everyday workflows, the need for critical engagement will become more pressing. These systems are persuasive and often convincing, but they are not inherently accurate or wise. Without the skills to assess, challenge and contextualise their output, users risk being misled—or misusing them.

This is why learning must be placed at the heart of digital transformation. Not technical onboarding, and not digital literacy alone but real, sustained learning—of the kind that strengthens cognition, improves metacognitive control, and enables creative problem-solving in the face of uncertainty.

If we want AI to succeed in the long term, we need to centre human learning—not as an afterthought, but as the foundation. This isn’t a call to slow down digital transformation but one to strengthen it by building in the human architecture needed to make it sustainable. That’s what cognitive alignment is about. And that’s what the next phase of AI adoption demands.

Because in the end, intelligence doesn’t live in the system. It lives in the person who knows how to use it.

Dr. Sarah Chardonnens is a Swiss-based professor of educational science at the University of Teacher Education Fribourg. An expert in metacognition, learning design and responsible AI integration, she works with institutions and businesses across Europe to support ethical, human-centred approaches to digital transformation. She is the author of The Learning Revolution – SYNAPSE Model.

Further information

www.sarahchardonnens.ch

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s -

Zanzibar’s tourism boom ‘exposes new investment opportunities beyond hotels’

Zanzibar’s tourism boom ‘exposes new investment opportunities beyond hotels’ -

Gen Z set to make up 34% of global workforce by 2034, new report says

Gen Z set to make up 34% of global workforce by 2034, new report says -

The ideas and discoveries reshaping our future: Science Matters Volume 3, out now

The ideas and discoveries reshaping our future: Science Matters Volume 3, out now -

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars -

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

European Commission issues new cancer prevention guidance as EU records 2.7m cases in a year

European Commission issues new cancer prevention guidance as EU records 2.7m cases in a year -

Artemis II set to carry astronauts around the Moon for first time in 50 years

Artemis II set to carry astronauts around the Moon for first time in 50 years -

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own -

Wingsuit skydivers blast through world’s tallest hotel at 124mph in Dubai stunt

Wingsuit skydivers blast through world’s tallest hotel at 124mph in Dubai stunt -

Centrum Air to launch first European route with Tashkent–Frankfurt flights

Centrum Air to launch first European route with Tashkent–Frankfurt flights -

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds -

Stanley Johnson appears on Ugandan national television during visit highlighting wildlife and conservation ties

Stanley Johnson appears on Ugandan national television during visit highlighting wildlife and conservation ties -

Anniversary marks first civilian voyage to Antarctica 60 years ago

Anniversary marks first civilian voyage to Antarctica 60 years ago -

Etihad ranked world’s safest airline for 2026

Etihad ranked world’s safest airline for 2026 -

Read it here: Asset Management Matters — new supplement out now

Read it here: Asset Management Matters — new supplement out now -

Breakthroughs that change how we understand health, biology and risk: the new Science Matters supplement is out now

Breakthroughs that change how we understand health, biology and risk: the new Science Matters supplement is out now -

The new Residence & Citizenship Planning supplement: out now

The new Residence & Citizenship Planning supplement: out now -

Prague named Europe’s top student city in new comparative study

Prague named Europe’s top student city in new comparative study -

BGG expands production footprint and backs microalgae as social media drives unprecedented boom in natural wellness

BGG expands production footprint and backs microalgae as social media drives unprecedented boom in natural wellness -

The European Winter 2026 edition - out now

The European Winter 2026 edition - out now -

Parliament invites cyber experts to give evidence on new UK cyber security bill

Parliament invites cyber experts to give evidence on new UK cyber security bill -

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change -

AI boom triggers new wave of data-centre investment across Europe

AI boom triggers new wave of data-centre investment across Europe -

Lammy travels to Washington as UK joins America’s 250th anniversary programme

Lammy travels to Washington as UK joins America’s 250th anniversary programme