Rekindling democracy’s promise in Europe

The region is confronted with great challenges that sometimes make the promise of democracy seem like a mirage that escapes from focus. Over thirty years after the fall of the Berlin wall, the rejuvenation felt about the dawn of democracy in Central and Eastern Europe has dissipated to a considerable degree.

Gradually over time, regimes such as in Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria and Serbia have taken actions curtailing civic space, undermining checks and balances, or concentrating power in the hands of a handful few. Populist politicians and aspiring authoritarian leaders are encouraged by the divisive politics within mainstream political parties. Inspired by modern role models, they feel emboldened by blatant attacks on civil liberties by seasoned autocrats such as President Recep Tayyip Erdogan or President Vladimir Putin.

Democracy’s expansion and the accompanying enthusiasm of the 1990s was followed by a more sober assessment of its dividends in the 2000s. By the end of this third decade since the fall of Communism, scepticism has set in and political leaders openly talk about preferences for more illiberal forms of democracy. Political regimes from Poland to Hungary, from the Czech Republic to Serbia, Romania and Bulgaria, have made retreats from the liberal notions of democracy by branding them as Western impositions. By doing so, have been stripping democracy of its many constitutive attributes in favour of a more minimalistic version of it built around the act of free and fair elections.

Nevertheless, this means regimes are using election results as a carte blanche to exert uninhibited power without too many cumbersome layers of checks and balances. And in the process, they tend to assault the judiciary, weaken parliamentary oversight, interfere in independent media, and stifle civil society and freedom of expression. As a result, although the region of Central and Eastern Europe remains democratic, this past decade has not brought significant advancements in the quality of democracy. Instead, the phenomenon of democratic backsliding has been chipping away at the region as a constant reminder of a creeping authoritarianism and populism.

Civil and political liberties: a luxury we can do without?

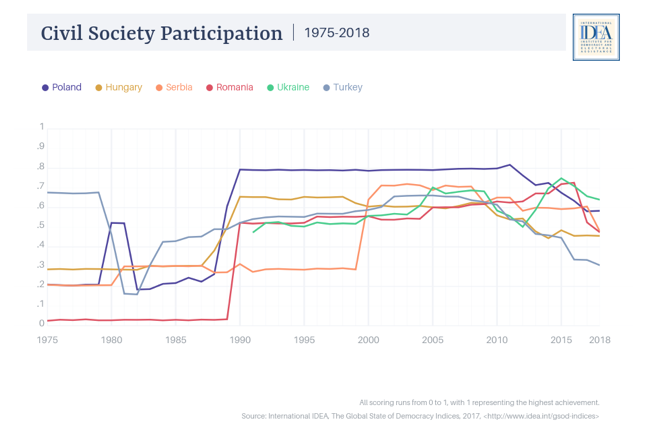

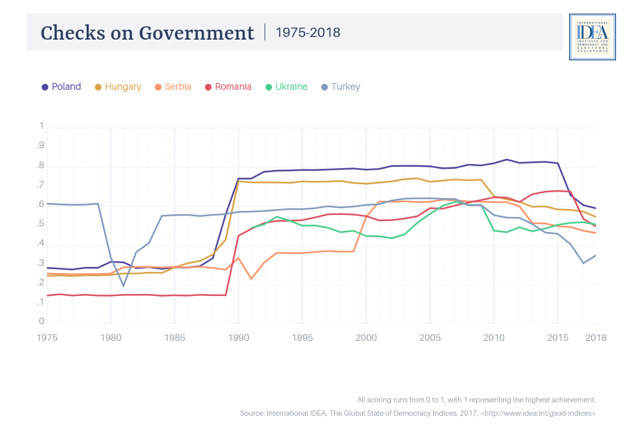

The 2019 report “The Global State of Democracy: Addressing the Ills, Reviving the Promise” from the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), dedicates a chapter to the state of democracy in Europe. It provides a health-check on the current democratic trends in Central and Eastern Europe and some diagnostics on the identified challenges. The analysis finds that more than half of democracies in Europe suffer from democratic erosion. Even more worrisome, six out of 10 democracies in the world that currently experience democratic backsliding are in Central and Eastern Europe (Hungary, Poland, Romania, Serbia, and to a lesser extent, Ukraine), and Turkey. Democratic backsliding here is defined as the intentional weakening of checks on government and civil liberties by democratically elected governments. The data from International IDEA shows that the regimes in the above countries have been intentionally curtailing parliamentary oversight and the independence of the judiciary as a way to accumulate more power for the executive. Further, they have taken steps to limit freedom of speech and freedom of expression and are stifling civil society’s room for manoeuvre.

Democratic performance on Checks on Government and Civil Society Participation for Poland, Hungary, Serbia, Romania, Ukraine and Turkey from 1975 to 2018*.

As they view it, such actions are taken to expedite government procedure, without the hassles of active opposition. Liberal notions such as freedom of speech, freedom of expression and freedom of association, on the other hand, are construed as foreign implants whose real aim is to frustrate the business of daily governance. This dangerous trajectory that shows all the signs of democratic backsliding is one of the main reasons why the quality of democracy has stagnated in the last decade in Europe.

Despite that, democratic backsliding may not necessarily end in an authoritarian political regime. Democratic legitimacy continues to be a requirement and constraint of incumbents acting to monopolize power. However, weakened checks and balances harm the substance of democracy: they enable incumbent governments to avoid public blame for policy failures, sustain unsubstantiated performance claims, and practice exclusionary decision-making. Moreover, unchecked executives can appropriate state resources for partisan or private purposes and expand informal patronage networks of loyalists to penetrate society.

The answer is, and should continue to be, the people

How is democratic backsliding reversed? At times of political uncertainty and social polarization, when some governments do not necessarily seem to be bulwarks of liberal democracy, who do we turn to? What is the remedy that will most effectively fight the democratic malaise? The answer: The people.

However, there is a problem with this recommended solution. Suggesting that the people will reawaken the liberal values of democracy tends to ignore the fact that it is the people who voted for those political leaders who are putting at risk those liberal values. Therefore, the question that ought to be explored is why people are voting for those leaders that end up eroding liberal values in the first place. In other words, relying on “the people” as a panacea for all societal ills, without understanding the underlying causes of democratic backsliding and authoritarian encroachment, tends to become a rather a lazy and quickly-uttered solution by opinionmakers to problems which are more complex and require deeper dissection.

Yet, people are the solution. Of course, the formula for more equitable representation, more accountability and transparency, and more emphasis on the liberal tenets of democracy, lies within the people. However, we should also recognize that the mainstream political parties are to a large degree responsible for losing electoral support as they have not been sufficiently attentive and responsive to the concerns of all citizens. These parties need to renew their engagement with their electorates. Decentralized and inclusive deliberation and decision-making within parties is one way to bring people back in.

However, party leaders and party representatives holding public offices also need to revise public policies that meet citizens’ expectations. In particular, policies should reach out to those groups of society that have felt excluded from decision-making and from the fruits of economic development. Responsive policies are not tantamount to myopic spending or fiscal irresponsibility. Policy trade-offs and cost-benefit considerations can be explained to citizens, so as to ensure a sound knowledge basis for informed choices. Political elites should engage in rational, problem-solving dialogues with citizens. These public consultations should be guarded by procedural and institutional arrangements preventing misinformation or demagoguery.

When such actions are undertaken by politicians and mainstream political parties, the people’s choice will be clearer too. Establishing appreciative, considerate dialogues between political representatives and citizens is the promising strategy to revive citizens’ trust in political institutions. In contrast, populist politicians usually substitute meaningful dialogues with fictitious claims about understanding the will of “the ordinary people”. Electoral majorities are then re-interpreted as popular mandates to ignore and erode institutional checks and balances, promising policies that will serve “the people” directly. To address populist challengers, supporters of democracy need to disclose such pretensions. Only then can they light a path toward a more responsive democracy and stronger institutions with mechanisms for democratic accountability.

For more Banking & Finance news follow The European Magazine.

Reported by Armend Bekaj & co-authored by Martin Brusis

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices, https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices/#/indices/world-map

Armend Bekaj is a Senior Programme Officer with International IDEA’s Democracy Assessment and Political Analysis Unit.

Martin Brusis is Senior Programme Officer with International IDEA’s Democracy Assessment and Political Analysis Unit.