The NHS should be held to account for its failings but medical memoirs that sensationalise its mistakes could be causing patients more harm than good, writes Dr Colin Stern

Medical memoirs attract readership. People find the adversity of others vicariously fascinating, perhaps from a sense of relief that it hasn’t happened to them (yet!). So long as there is some humour in the story, these books sell very well.

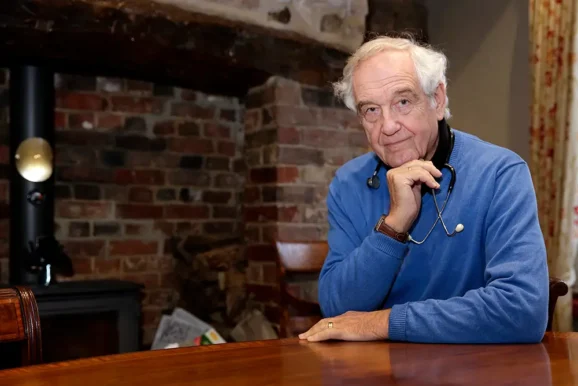

“Do No Harm,” by Henry Marsh, treads the line sure-footedly between the drama and stress of neurosurgery modulated by his compassion, and the abyss of titillating tragedy into which medical authors can fall.

But while some medical memoirs offer a balanced picture, others use the drama and dark humour of medical failings to create a book which, while immensely entertaining, paints a picture of a dysfunctional health service, provided by careless, ignorant and incompetent medical staff.

A more human picture of health care is offered by interviews with families and patients who have passed through the hands of doctors and nurses providing competent, caring and compassionate support. Stories such as these appear from time to time in the national newspapers. While the medical detail is frequently less than accurate, the joy and relief of those who have gone through such stressful experiences shine through.

Our National Health Service is going through a period when it seems to be teetering on the brink of collapse. The causes have been variously ascribed to the Covid-19 pandemic, increasing demand, misguided reorganisation, inadequate and dilapidated hospitals and underfunding. However, the underlying problems are quite simple.

Successive governments have screwed down the numbers of trainees to save money. At one point, Britain had fewer doctors and nurses per head of population than any European country, other than Albania. Numbers are still far lower that our neighbours. Social care is overburdened. There are approximately 30 per cent more administrators than we need and too few of the ones in post have any background in health care provision at the coal face. It is hardly surprising that waiting times are lengthening and bed blocking increasing.

On top of this is the loss of trust in healthcare providers that is, I’m sure, connected to sensationalist medical memoirs. Such books are contributing to a climate of fear, making the public more anxious about those who are caring for them than they need to be.

A trainee of mine spent six months working in an Italian hospital. While she was there, a local surgeon amputated the wrong leg. When my colleague remarked upon this, one of her fellow trainees commented that matters were far worse in the NHS, citing various errors that had been highlighted by the British press. My trainee pointed out that there had been no mention of the Italian surgeon’s mistake in the Italian newspapers. “That’s the difference,” she told me. “When things go wrong in Italian medicine, you rarely hear about them.”

Obviously, this is not the best way to deal with medical mistakes. Medical failings ought to be exposed to both the profession and the public. That’s how medical care improves.

It’s true that reorganisation of the NHS is always painful, but it should be led by healthcare providers. Andrew Lansley’s reforms were misguided, largely because they seemed to be based on several misconceptions about what was amiss and how it could be improved. Having spent over forty years working in the NHS, I think I have a fairly good idea about how to make it work better. So let’s have lots of experienced nurses, doctors and ancillary workers sorting it out.

Democracy depends upon the independence of politics, the law, religion and the press. Without those freedoms no population can rely on the stability of their country. I would be strongly against any constraint being placed upon the expression of opinion, no matter how much such an opinion might offend me. If I don’t hear it, I can’t react to it. Recent campaigns, often led by students, to block uncomfortable views on Israel, LGBTQIA+ comments, puberty blockers and so on are misguided, because they stifle debate. Students in particular ought to listen and only then criticise, otherwise how will they develop their own views?

So how may we present a more balanced view of the National Health Service? Good news stories are often said not to be newsworthy but, in healthcare, this isn’t the case. Reporting how patients can be healed, or at least helped, can be dramatic and entertaining at the same time.

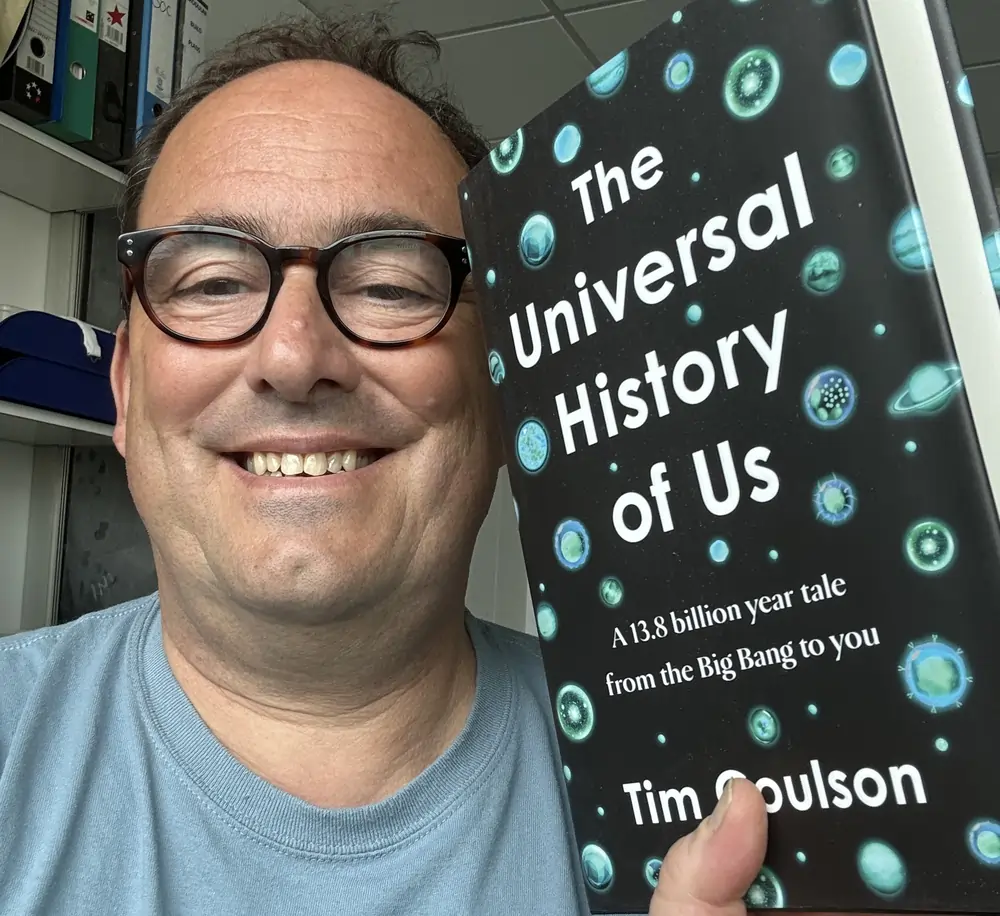

When I published Listening to Mother, a collection stories about children I had met as a paediatrician, my hope was that they might be appreciated by the public. While not all these stories have happy outcomes, many of them do. As my daughter said, “Listening to Mother is an antidote to negative medimoirs.” But it has always seemed to me that former doctors who write books like this should have stayed in the NHS and done their best to provide medical care of a higher standard than we read about in their pages.

Another question that authors should ask themselves before publishing a medical memoir is whether anyone, or for that matter the National Health Service, might be hurt by their writing.

All doctors know that they should ‘do no harm’ and do their best to follow that principle. In that light, they should examine their own conscience before writing sensationalised medimoirs. Criticism is healthy, but when criticism becomes calumny, it can be injurious.

As a firm believer in freedom of speech, I leave it entirely to physicians to reflect on the morality of penning a sensational medical memoir, but the implications are serious. As people delay treatment because of theirs concern about the NHS, minor health issues can become severe.

This, in turn, increases emergency room visits, leading to higher overall healthcare costs and demands that further strain an already fragile healthcare system.

These issues are then grist to the mill for doctors writing sensational medimoirs, whose unbalanced accounts, emphasising failures over successes, lead to people becoming even more anxious about seeking medical help.

Medical care is all about turning distress into relief and those who try to provide it dedicate their lives to do so. We should hear about their mistakes and do our best as a nation to put them right. We ought also to celebrate their successes and rejoice in the recovery of their patients.

Dr Colin Stern is the former Clinical Director of Paediatrics at St Thomas’ Hospital and Postgraduate Dean at Guys & St Thomas’ Hospital. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine and was President of its Paediatric section between 1990 and 1992, as well as the Chair of its Academic Board from 1994 to1996. Dr Stern, who qualified as a doctor in 1966, retired from the profession in 2006. His acclaimed book, Listening to Mother, out now, highlights some of his most interesting and unusual medical cases, and celebrates the tireless work of those dedicated treating and caring for children.

Main image: Courtesy Karolina Kaboompics/Pexels