Better than the real thing?

To underestimate the power of imitation is to miss a truly golden business opportunity, says Jan-Michael Ross of Imperial College Business School

Last year, European supermarket giant Aldi found itself in hot water in the UK when British retail competitor Marks & Spencer brought legal action against the company over the sale of a cake.

The new product, launched by Aldi, consisted of a chocolate swiss roll cake designed to look like a caterpillar. Whilst not an uncommon idea (most UK supermarkets sell similar cakes) Marks & Spencer’s complaint was that, in fact, Aldi’s cake had been designed to look like a very specific caterpillar cake – their own much-loved Colin, which has been a firm favourite with customers for many years. Aldi had imitated Colin’s design so closely, they said, that customers were becoming confused, losing Marks & Spencer customers. Even Aldi’s packaging and cake name (Aldi’s caterpillar is named Cuthbert) had been imitated. Arguably, the only noticeable difference was the price – with Aldi’s coming in markedly cheaper.

On this occasion, M&S came out of legal proceedings on top, with Aldi forced to concede that the resemblance between Cuthbert and Colin was, perhaps, a bit too close. But this is a road Aldi has travelled, and successfully navigated, many times before. It’s entire business model is built upon attempting to emulate popular products – from groceries to garden furniture – and selling them at a fraction of the cost. It’s a strategy which has brought the company significant success.

Imitation is everywhere – from fashion retailers such as Zara, Primark and, now, Shein building a solid customer base by providing swift cheap dupes of luxury label designs, to the more mundane vacuum cleaners and floor mop designs. For years, musicians have enjoyed successful careers performing as tribute acts, while artists and songwriters are adept at adapting old ideas to create something new. As the famous saying goes, “good artists copy, great artists steal”. Either way, it’s clear that copycat behaviour can be an effective tool in finding swift success.

Imitation also brings stability – not only do you have something of a sure-fire means of estimating how well your customer base might react to your offering, it also provides a layer of reassurance for investors especially when considering whether to support untested start-ups. In fact, when used deftly, imitation can speed up the pace of change, spark innovation and leverage creativity.

But despite the benefits – copycat behaviour often leaves a bad taste in the mouth of those who witness it. Terms such as “imitate” and “replicate” bring with them preconceptions which lead the wider business arena to perceive any type of imitation as a weak or limiting strategy. Imitation, it is thought, can only ever accomplish being as good as (but never better than) the real thing. In contrast, the concept of originality is one that is revered. Aspiring business leaders are encouraged to develop the skills to become the next Jeff Bezos or Mark Zuckerberg in order to accomplish any real success. LinkedIn profiles of business school graduates are far more likely to contain accolades of being “leading innovators” rather than “leading imitators”.

A question of innovation

But is there such a thing as true innovation anymore? Harvard economist Professor Theodore Levitt pointed out more than fifty years ago that we “often mistake innovation for what is really imitation”. More recently, the equally revered Stanford Professor James G. March observed “imitation probably represents the majority of what is normally called innovation”.

So what can we do to change the narrative? My research, undertaken with colleagues Stefano Benign at Imperial College London), Hart E. Posen of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Brian Wu of the University of Michigan, and Zhi Cao of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, seeks to redefine what can be gained by adopting a culture of Strategic Imitation.

Why imitation works

Strategic Imitation, we define as when a firm purposefully attempts to reproduce (in whole or in part) another firm’s products, processes, capabilities, technologies, structures, or decisions, in its pursuit of finding a competitive advantage.

We review the origins and implications of these assumptions to expose a set of emerging counter-assumptions, using these findings to propose the foundation for a new, respected model of imitation that focuses on evolutionary dynamics, helping to drive innovation and, in turn, giving rise to better competitive advantage. It is not only smaller firms looking for a swift leg up that can benefit. In the right climate, imitation benefits even the heftiest players.

Our dynamic model acknowledges the fact that imitation is difficult, takes talent to pull off effectively, takes strength and can provide a source of disequilibrium for firms and industries.

To encourage such a shift in perception, the first step is challenging three commonly help assumptions about imitation:

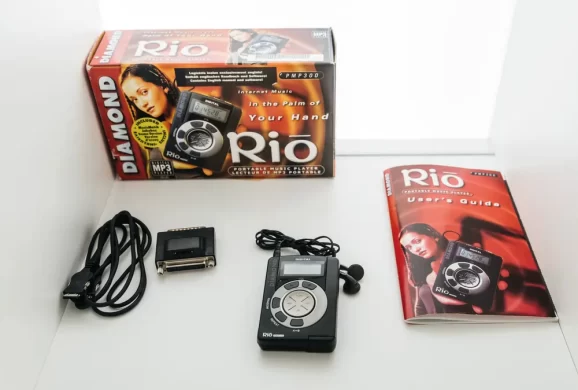

- Imitation is a sign of weakness – Our research shows that often, world leading firms often use imitation as a strategy when faced with competition from smaller, more innovative firms. Whether P&G launching a brand new “Swiffer” mop in 1999 to great success when a smaller Japanese firm had already sold a similar item for many years or, more recently, claims that Apple’s original iPod was in fact based upon the physical design of an earlier competing music player – the Diamond Rio. The power of these larger firms enabled them to exploit smaller relatively unknown inventions and benefit from the assumption that these innovations were in fact their own.

- There is only one way to imitate – We widely assume that imitation takes little creative planning or thought, or even the need for any initiative as the blueprint has already been laid out for others to follow. Surely the only choice in the imitation process is asking “do we copy this?” and deciding “yes” or “no”. However, choosing who, what, when and how to imitate requires significant skill and judgement in order to ensure success. There is further decision to be made in how to adapt existing ideas so that the imitation product offers something different, better, to customers. This latter point is vital for shifting the current imitation narrative – as being able to copy and grow ideas, and the speed at which this is done at, can influence how competitors respond, creating a more dynamic marketplace.

- Imitation is easy – Similar to the point above, it is widely assumed that imitation involves little more than copying and pasting someone else’s ideas or activities, and benefitting from it (a perspective that drives the “lazy” preconception). Such perspectives do not do justice to the complexity of the process. Much of effective imitation relies on developing good business instincts and developing a curious team. For example, the methodology of the technologies a company might seek to replicate may be opaque or secretive and therefore difficult to copy. Companies have to resort to investigations, guesswork and their own ingenuity to replicate and build upon existing ideas. Aside of this, the ability to understand why a brand or product is popular is vital for ensuring a similar product can also find success.

The stark reality is that to underestimate the power of imitation is a business opportunity missed. Used correctly, Strategic Imitation can become the source for building greater capabilities and driving innovation.

About the Author

Dr Jan-Michael Ross is Associate Professor of Strategy at Imperial College Business School.